Victorian computer boffins become crime-fighters in Lovelace and Babbage, the iPad comic app. We talk to developer Dave Addey.

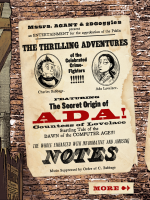

What’s the best way to take the story of two Victorian computer pioneers and turn it into an exciting iPad app? How about re-imagining their story as a comic book adventure and turn them into Victorian crime-fighters solving mysteries on behalf of the Queen? Well that’s what brilliant Canadian artist and writer Sydney Padua did and thanks to the guys at Agant it’s now a fantastic interactive app. Released to commemorate Ada Lovelace Day on October 7th (a day started to celebrate the role of women in technology) this brilliant app is a slice of steam punk style Victoriana, a bit like the League of Extraordinary Gentleman meets Dempsey and Makepeace, but also features interactive historical annotations along the way so you can really get a feeling of just how intricate and accurate the story-telling is. To find out more about this fantastic new crime-fighting duo and their historically accurate adventures, I got in touch with app developer Dave Addey and asked him where the inspiration for this great new app came from…

What’s the best way to take the story of two Victorian computer pioneers and turn it into an exciting iPad app? How about re-imagining their story as a comic book adventure and turn them into Victorian crime-fighters solving mysteries on behalf of the Queen? Well that’s what brilliant Canadian artist and writer Sydney Padua did and thanks to the guys at Agant it’s now a fantastic interactive app. Released to commemorate Ada Lovelace Day on October 7th (a day started to celebrate the role of women in technology) this brilliant app is a slice of steam punk style Victoriana, a bit like the League of Extraordinary Gentleman meets Dempsey and Makepeace, but also features interactive historical annotations along the way so you can really get a feeling of just how intricate and accurate the story-telling is. To find out more about this fantastic new crime-fighting duo and their historically accurate adventures, I got in touch with app developer Dave Addey and asked him where the inspiration for this great new app came from…

How did you come up with the idea for the app? Was it a story you wanted to tell or an app you wanted to make?

I’m an interface designer by trade, and have been a comics fan for years, so I saw the iPad as an opportunity to do something genuinely new with comics. However, I’m not an artist, so my ambitions had to wait until I could find someone willing and crazy enough to collaborate on an actual experimental comic. Thankfully, a large dose of serendipity meant that this happened early in 2011, which in turn led to the launch of the Lovelace & Babbage iPad app this October.

How did you get in touch with the artist and what do you think was the best thing that they brought to the project?

I first met Sydney at The Story (http://thestory.org) in 2010, where she spoke about her own approach to comics composition and storytelling. I then randomly bumped into her a year later at Earl’s Court tube station, which led to a long and rambling conversation about comics, iPads, and annotated works. This in turn led to a hack weekend at the Agant offices early this year, where we experimented with the form of the iPad to see what comics storytelling tricks we could create to suit the device, without losing the essence of what makes comics comics.

This hack weekend produced a whole bunch of possibilities for the comics medium, all of which were specifically designed to work on an iPad. We had grand ambitions for bringing these to the device in time for October this year; these ambitions were tempered somewhat by Sydney’s day job as a Senior Animator on John Carter From Mars during the summer. As a result, we decided to focus on one particular aspect for our initial release.

Sydney’s original webcomic is supported by copious historical annotations and primary documents, which don’t have the impact they deserve when positioned underneath a scrolling webcomic. So, we decided to produce a version of Lovelace & Babbage which gave equal billing to these notes, and which brought the supporting documents to life. I’m particularly pleased with how the app focusses solely on the comic in portrait, but shows both the comic and the notes in landscape.

Apart from being a talented writer and artist, the best thing about Sydney is that she has great ideas for experimenting, balanced by a strong sense of what works and what doesn’t. We’ve set ourselves a principle for these experiments: whatever we create, it still has to be comics. It’s not a game, or an animated cartoon, or a book; it’s a comic. As an experienced 2D artist and animator, Sydney understands the medium perfectly, and is great at keeping our experiments true to the medium.

Was the artwork produced digitally? If so, how, is it all on a Mac/PC or is it actually done on an iPad?

Sydney produces all of the artwork on a Mac using a 21″ Wacom Cintiq, which is a brilliant piece of kit combining a tablet pen and a monitor into one gadget. She can draw directly onto the screen with full brush effects and pressure, and export the result as high-resolution layered digital artwork.

This artwork is then lettered and converted into a series of flat images, ready for annotating and structuring into the actual comic. For this part of the process, we created a custom set of desktop tools for Sydney to use on her Mac. Our aim has always been for the artist to have creative control over the comic – this goes for the annotations too. These tools allow Sydney to import the original artwork, define the panel borders used when focussing on individual panels in the notes, write the historical annotations, and attach documents and engravings to the notes. We also set Sydney up with Apple’s Xcode development tools, so that she could build the app itself and see how the comic was taking shape as she worked, without having to ask us to create new builds all the time.

Whats the next step, are you planning more Lovelace and Babbage stories or what about other comic style biography apps?

Now that John Carter has wrapped, Sydney is working on a brand new Lovelace and Babbage story, User Experience, created specifically for the iPad. This will feature of many of the new tricks from our original hack weekend, including a paged infinite canvas, multiplane camera reveals, spot animations, hidden pages and atmospheric background audio. We’re particularly pleased with how the 2D infinite canvas is working out on the iPad – especially for a story that’s being composed specifically for the device. We’re expanding the tools from v1 to support these additional features too, so that Sydney can continue to control the creative process.

In addition to the new comic and tools, we’d love to use our existing annotations engine to create a full-length annotated graphic novel for the iPad. One inspiration for the current app was Alan Moore’s From Hell, which includes extensive annotations at the end of the book. However, due to the physical form of the book, these notes suffer by being physically removed from the pages they annotate – something we can fix on the iPad. It would also be interesting to use the engine to annotate a complex work such as Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles – I could see Patrick Neighly’s Anarchy For The Masses working well alongside the original artwork in this case.

We’re also looking to apply the annotations engine to other media – it would work just as well for annotating prose or historical manuscripts, say. One of our inspirations when creating the Annotations Engine was Martin Gardner’s seminal The Annotated Alice – we’d love to bring an annotated book to life in a similar way.

Did you always plan to release it on Ada Lovelace Day and who do you regard as you favourite female technology pioneers?

We wanted to release v1 of the app on Ada Lovelace Day to raise awareness of the day itself, and also to tell the world about Ada and her history.

As an interface designer, one of my great heroes is Florence Nightingale. She may be best known for revolutionising the treatment of war casualties, but she also pioneered the use of infographics to communicate important messages, and invented a variant on the pie chart to communicate the effects of poor medical care in the Crimean War.

What do you think of other comics apps like Comixology, what are you reading at the moment and do you read them on the iPad?

I’m a big fan of the Comixology iPad app, and buy nearly all of my comics through their store. However, Comixology is all about converting existing print comics for digital reading (which it does very well), rather than creating comics for the form of the device itself. It’s an acceptable replacement for printed comics – although the iPad is slightly smaller than a standard print comic, which means that text is a bit small on screen. Nonetheless, instantaneous purchase and delivery, and portability for when you have a spare moment on the train, definitely outweigh the slight size discrepancy.

I’m not a fan of the panel-by-panel progression approach used in Comixology for reading print comics on a smaller screen such as an iPhone. It’s a clever approach, and it’s the only way to make existing print comics work for that form factor, but it loses the impact of the page as a whole. As Scott McCloud notes in Understanding Comics, a comic isn’t just about the contents of the panels – it’s about the space between the panels, and the temporal tweening the reader’s brain performs when reading a sequence of panels as page. Panel-by-panel navigation loses the overall composition of the page, which is a big part of what defines comics as a medium. I should stress that this isn’t a criticism of Comixology – it just an intrinsic problem with trying to view works composed for a comics-sized page on an iPhone-sized device.

My current favourite comic is John Layman and Rob Guillory’s Chew, new issues of which really can’t come soon enough. And I’ve just finished reading Bastien Vives’ short graphic novel A Taste Of Chlorine, which is now available in English – it’s a great example of the power of simple images and strong composition to communicate emotion with an absolute minimum of dialogue.

What do you think is the secret to a good app? Both as a developer and as a consumer? And what are some of your favourites?

Most of all, an app should delight the person using it. It should work exactly as you expect, even if you’ve never used it – there’s no such thing as a stupid user, just a badly-designed app. And it should have hidden delights to be discovered – the kinds of things that make you smile when you find them.

As for my favourite iPad apps… assuming I can’t choose our own, I’d go for:

• Plants vs Zombies, for its humour and ability to gnaw through many hours of my spare time

• Osmos, for creating a totally immersive gameworld through visuals and audio alone

• The Guardian, for genuinely reinventing the newspaper to suit the form and function of an iPad

• Tap! Magazine, for doing the same for magazines

• Three Little Pigs, for taking the form and capabilities of the device, and creating something so well suited to them that you don’t even notice it’s a book

• Toca Hair Salon by Toca Boca, who make digital toys that encourage kids to play creatively without enforcing a rigid game structure

• Garageband, for making music creation available to anyone and everyone, regardless of musical ability

All of these are intuitive and pleasurable to use, and all of them delight the user. If we can achieve the same for iPad-native comics, we’ll know we’ve done our job.

You can download the Lovelace and Babbage app here or follow Dave on twitter @daveaddey

December 21, 2025 @ 12:56 am

Auch wenn es großen Spaß macht, in einem Online Casino zu spielen, hat es natürlich

einen ganz besonderen Reiz, ein reales Casino zu besuchen. Sie können Roulette, Blackjack sowie die schweizerische Variante Swiss Jack, Big Shot und Poker an den Spieltischen spielen. Den Klassiker Roulette können Sie mit

Einsätzen ab 2 Franken (an Wochenenden ab 5 Franken) spielen.

Sie entscheiden, ob Sie Poker, Bingo oder Roulette auf moderne Art spielen wollen. Hier spielen Sie komfortabel

und bequem mit Touchscreen-Bildschirm Roulette. Auf Glücksspieler warten Roulette, Blackjack und Poker sowie natürlich spannende Spielautomaten und Jackpot Automaten. Wenn du dich entscheidest,

um echtes Geld zu spielen, stelle bitte sicher, dass du nicht mehr spielst, als du es

dir finanziell leisten kannst zu verlieren. Casinospieler erhalten präzise

Informationen über sichere Online-Glücksspiele und Online-Casinos in der Schweiz.

Dank seiner Erfahrung und fundierten Kenntnisse in diesen Bereichen liefert

er wertvolle Informationen für Casinospieler in der Schweiz.

Die aktuellen Zeiten finden Sie auf der Website

des Casinos. Das Coco bietet Ihnen eine herrliche Aussicht auf den Kurpark.

In stilvollem Ambiente finden Sie wechselnde Menüs, raffinierte

Desserts und eine ausgezeichnete Weinauswahl. Es gibt auch einige

vernetzte Jackpot-Spiele, darunter zum Beispiel der Lions Jackpot und der Swiss Jackpot.

Für Pokerfreunde bietet die Spielbank eine umfangreiche Auswahl an Cash Games und Turnieren.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/verde-casino-50-freispiele-sichern-angebot-details/

December 26, 2025 @ 2:47 pm

Our support team is always ready to assist you with queries or issues.

We constantly update our game library with the

latest titles from top providers to ensure you have

various choices. Please don’t waste any

more time and start enjoying everything that we at

Skycrown Casino Australia have prepared for

you; after all, we feel like you are already home!

With this in mind, Skycrown Casino Australia has a support team

for our users, with professionals available to answer any

questions or listen to suggestions for improvements. Everyone can find

a place on our platform, from traditional gamers

to those who love to innovate. Play Live Games and get 1 point per every A$75

wagered (real money only).

Fair Terms & Transparent BonusesWatch out for bonus traps!

And make sure withdrawal times are clearly stated and reasonable.✅ 5.

Look for platforms that support AUD, Neosurf, crypto, and e-wallets like

Skrill or Neteller. If you see names like NetEnt, Pragmatic Play,

Microgaming, or Evolution, that’s a very good sign. The world of online gambling is bigger than ever, especially in Australia.

Just open the site in your mobile browser and jump right into the action.

If you want to feel like you’re on the casino floor, Live Roulette is

where it’s at. With a mix of sparkling jewels and flashing lights, it’s an absolute ripper for pokies lovers looking for a

bit of explosive fun. This game is deadset famous for dishing out massive,

life-changing prizes. If you’re chasing that life-changing jackpot,

Mega Moolah is the one to play. At SkyCrown, quick withdrawals get your winnings in your hands faster than a grey ghost on a hot streak.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/instant-withdrawal-casinos-australia-15-fast-payout-casino-sites/

December 27, 2025 @ 1:17 am

No need to jump through hoops or deal with confusing systems –

just straight-up fun and fair play. Just pure casino fun, wherever you are.

The sign-up process is fast, payments are secure, and the support team is

always available. These allow the platform to collect

useful info about visitor preferences and behaviours.

You can reach them via live chat or use the “Contact Us” form

for more detailed queries.

Get your casino journey started with double your money and spins on popular pokies like Book of Dead and Big Bass Bonanza.

Whether you love spinning pokies or prefer classic table games, this offer gives you the freedom to explore and win from

day one. Whether you’re using a Samsung, iPhone, or anything in between, you’ll get a premium gambling experience that fits

right in your pocket. Currently we only offer live chat and email support,

no phone assistance. Looking for a trusted and exciting

online casino in Australia? Your ultimate destination for premium online gambling

in Australia

References:

https://blackcoin.co/casino-winning-odds-best-and-worst-games-chances-to-win/

December 29, 2025 @ 4:53 am

online casino that accepts paypal

References:

https://starlikekorea.com

December 29, 2025 @ 8:01 am

casino paypal

References:

https://payment.crimmall.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=138568