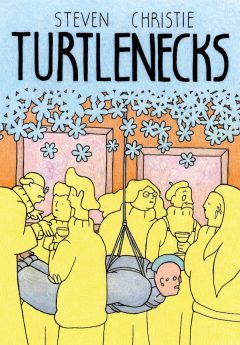

Review: Turtlenecks (AdHouse Books)

How is your identity constructed? What makes you special? For art student Sam, the subject of Steven Christie’s new graphic novel Turtlenecks, it’s his striking blue flower that he proudly wears every day. But when the flower accidentally sells at an art exhibition, Sam and his group of arty misfits must team up to commit a fabled heist.

Publisher: AdHouse Books

Publisher: AdHouse Books

Writer: Steven Christie

Artist: Steven Christie

Price: Available May 26th from AdHouse Books

In typical heist fashion, Turtlenecks begins its story with a problem that needs a quick solution. Author Steven Christie calls on his own experience as a gallery hopping art student and native Melbourne resident to set the scene. Our central duo Sam and Jules are attending an art exhibition intended to raise money for their school. Sam feels stuck and wants to redefine his identity, so carelessly puts his most beloved object (his blue flower necklace) up for sale. Never thinking that his necklace will actually sell, Sam is devastated to find that someone has bought it, and that he is unable to reclaim it. Inevitable chaos ensues, as the rest of the graphic novel focuses on the formation of the ‘turtlenecks’ – a heist-based performance art collective with one mission: to get Sam his flower back.

Turtlenecks clearly draws its inspiration from heist classics like Ocean’s 11 and Tower Heist, and if it intended to follow in their great footsteps, it did not disappoint. From its obscure references to spatio-temporal body typology (look it up!), which Steven Christie cleverly incorporates into the chapter dividers, and the character’s self-awareness in naming their own heist ‘flower heist’ (a pun on the aforementioned Tower Heist), Turtlenecks definitely honours its source material. We loved the incorporation of the heist recruitment gag, a typical trope used in heist films, as Sam and Jules set out to find their camera man and getaway driver. We also loved how Christie subverts the heist genre, including a humorous rather than typically serious moment when the group names themselves the ‘turtlenecks’ based on a bizarre idea to get matching turtle tattoos and accompanying adorable nicknames.

Turtlenecks clearly draws its inspiration from heist classics like Ocean’s 11 and Tower Heist, and if it intended to follow in their great footsteps, it did not disappoint. From its obscure references to spatio-temporal body typology (look it up!), which Steven Christie cleverly incorporates into the chapter dividers, and the character’s self-awareness in naming their own heist ‘flower heist’ (a pun on the aforementioned Tower Heist), Turtlenecks definitely honours its source material. We loved the incorporation of the heist recruitment gag, a typical trope used in heist films, as Sam and Jules set out to find their camera man and getaway driver. We also loved how Christie subverts the heist genre, including a humorous rather than typically serious moment when the group names themselves the ‘turtlenecks’ based on a bizarre idea to get matching turtle tattoos and accompanying adorable nicknames.

Each character is genuinely likeable and interesting to follow, and Christie takes the time to flesh each of them out. We really identified with Sam’s struggle to find his identity after his flower sold, and his frustration to try and reclaim something that should be his by right, but that he took for granted. His best friend Jules is a fantastically written non-binary character whose obscure references and bad-ass fighting moves really help the heist to go off with somewhat minimal hitches. Other members of the heist, Stacey, Casper and Ryan, contribute so much with their funny side comments. Stacey stating that she is in a meeting whilst chilling in her room with her teddy bears? Relatable. Casper’s being nicknamed the turtle ‘egg’ as a newbie to turtlenecks? Hilarious. And who can forget Ryan’s fabulous fashion style and total misunderstanding of the primary mission? On top of this, the fact that all of them get the date of the heist wrong is just hysterical.

We loved the pastel colour palette throughout, which gives the impression of being carefully hand coloured. The art pieces on display in the various gallery scenes are a treat unto themselves, and Christie doesn’t hold back on the weirdness: some of our favourites include a snooty dog with beret and a much sought-after painting of a milk crate. We also loved the transition scenes, in which a character or background would become an anthropomorphic blob, which slowly dissolves and transforms into an object from the upcoming scene.

We loved the pastel colour palette throughout, which gives the impression of being carefully hand coloured. The art pieces on display in the various gallery scenes are a treat unto themselves, and Christie doesn’t hold back on the weirdness: some of our favourites include a snooty dog with beret and a much sought-after painting of a milk crate. We also loved the transition scenes, in which a character or background would become an anthropomorphic blob, which slowly dissolves and transforms into an object from the upcoming scene.

One of the more obscure aspects which makes Turtlenecks so idiosyncratic is its blurring of the conceptual and the physical. Set in 2035, Christie lovingly satirises the art world by making art objects intrinsically bound to the concepts they represent. Sam’s flower is so valuable because of the meaning attached to it, rather than it being extraordinary physically: ‘it’s five for the flower. But for $6,000 you get the sense of loss, concerns of materiality…and heck, I’ll even throw in the historical context for free’. Throughout, the characters refer to a theory called ‘The Death of the Author’ when discussing their art pieces and their claim to them once they have been sold. This theory argues that the author (in this case, the artist) is merely a vehicle through which a work is transmitted, and that once it exists in the public domain, the author has no authority over it. This is a niche and fascinating concept to explore, and we applaud Christie for tackling such a tricky theoretical debate with such finesse.

There are so many other moments we want to mention (including an evil spirit level and a literal representation of interior time and space), but we hope you’ll pick up the book and experience its wit and warmth for yourselves.

February 5, 2026 @ 9:20 am

web signature capture https://otvetnow.ru sweat allergy