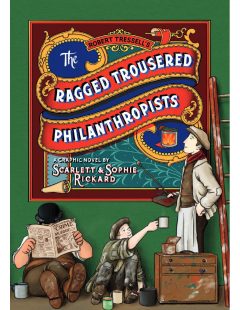

Review: The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (SelfMadeHero)

Imagine watching others undeservedly live in the lap of luxury due to their status whilst you struggle to pay the bills, get enough food to live, and provide for your family, working every day for a pittance. Would you think that this is fair? Protagonist Frank Owen certainly doesn’t think so in Sophie and Scarlett Rickard’s faithful graphic novel adaptation of Robert Tressell’s socialist novel, ‘The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists’.

Publisher: SelfMadeHero

Publisher: SelfMadeHero

Writer: Sophie Rickard

Artist: Scarlett Rickard

Price: £14.99 from SelfMadeHero

Sophie and Scarlett Rickard’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists follows the lives of a group of men in the 1900s living in the fictional town of Mugsborough, England. Forced to continue working for the sake of their families whilst barely earning enough to survive, the men begin to question the morality of their Capitalist government, and philosophical concepts about the rich and the poor. Aided by regular lectures from protagonist Frank Owen, the men are torn between the unfair world they’ve always known, and the socialist utopia that Owen promises.

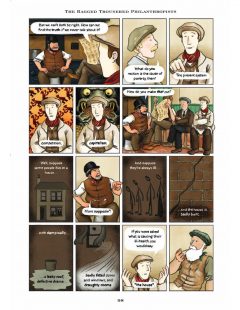

To give some context, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists is based on a semi-autobiographical novel of the same name written by Robert Tressell in 1914. The novel is well known for being an intrinsic piece of socialist history and was named ‘one of the most authentic novels of English working-class life ever written’ due to its depiction of corrupt capitalists and philanthropic workers. The name ‘philanthropists’ refers to the working men themselves, who believe that a better life isn’t available to them and continue to do dangerous work for a trifle whilst making a huge profit for their masters. The Rickard sisters do a fantastic job of remaining true to the original material, whilst making the story perhaps more accessible to a modern audience. Owen’s enlightening lectures on poverty shine in graphic novel format, as Scarlett Rickard’s illustrations carefully print out each individual analogy for the reader to understand.

Although the sheer number of workers focused on can be overwhelming and hard to remember at first, over the course of the next 350 pages, we get to know each of them intricately, thanks to their distinct personalities and looks. Amongst the central group of men, Frank Owen stands out, as he has a differing opinion about the state of Britain: he believes that poverty is the fault of the Tory government and capitalism, and that socialism is the only viable option for equality.

Although the sheer number of workers focused on can be overwhelming and hard to remember at first, over the course of the next 350 pages, we get to know each of them intricately, thanks to their distinct personalities and looks. Amongst the central group of men, Frank Owen stands out, as he has a differing opinion about the state of Britain: he believes that poverty is the fault of the Tory government and capitalism, and that socialism is the only viable option for equality.

In the context of modern politics, especially with the recent revival of socialist ideas, modern-day readers can empathise with Owen’s views. Not so for the philanthropists, who frequently laugh at the ‘outlandish’ views which differ from their own. It seems that only the reader and Owen himself can identify how poorly the working class are being treated by the rich, and how dire their circumstances are. Yet they seem content to stay this way, rather than change their views to what they see as radical, due to their education which teaches them to distrust their own thoughts and rely on their ‘betters’. Religion is also seen to contribute to this, with corrupt priests misquoting the Bible to suit their views that the poor should remain poor (& should be happy about it!) and conning them out of the money they do have to provide for the church (their own pockets).

Owen’s mini lectures about capitalism are often interwoven with other narratives to split them up; these are usually divided by chapters with vibrant template illustrations of an issue the chapter will be discussing (for example, a stained-glass church window in a chapter focused on religion). One of the most poignant secondary narratives focuses on one of the workers, Easton, and his home-life with his wife Ruth and their son. Forced to take on another of the philanthropists as a lodger due to their extreme poverty, they soon find themselves uncomfortable in their own home as Mr Slyme (aptly named) slowly seems to take over. This storyline sadly involves the assault of Ruth by Slyme, who takes advantage of her when she is drunk, resulting in an unwanted pregnancy. Unfortunately, this was a regularly occurring issue that was often swept under the rug due to the imbalance of rights between men and women.

Owen’s mini lectures about capitalism are often interwoven with other narratives to split them up; these are usually divided by chapters with vibrant template illustrations of an issue the chapter will be discussing (for example, a stained-glass church window in a chapter focused on religion). One of the most poignant secondary narratives focuses on one of the workers, Easton, and his home-life with his wife Ruth and their son. Forced to take on another of the philanthropists as a lodger due to their extreme poverty, they soon find themselves uncomfortable in their own home as Mr Slyme (aptly named) slowly seems to take over. This storyline sadly involves the assault of Ruth by Slyme, who takes advantage of her when she is drunk, resulting in an unwanted pregnancy. Unfortunately, this was a regularly occurring issue that was often swept under the rug due to the imbalance of rights between men and women.

One of the standout moments of this graphic novel is Owen’s elaborate painted designs for an aristocratic house. The men are so used to being boxed in as manual labourers that having this creative outlet is really refreshing to see. The gorgeous endpapers with tens of different paint brushes reinforces how important the task becomes to Owen. The art in general realistically depicts how the men are feeling, with a fantastic eye for facial expressions and subtle colouring to indicate emotion.

This is Sophie and Scarlett’s second graphic novel project together (see also the wonderful Mann’s Best Friend), and it’s clear that it’s a huge success! We hope to see more collaborations from the sisters in future!

August 15, 2025 @ 12:52 pm

Thank you for any other fantastic article. The place else may anyone get that type of info in such an ideal means of writing? I have a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at the search for such information. http://www.kayswell.com

August 15, 2025 @ 3:56 pm

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Many thanks, However I am encountering problems with your RSS. I don’t understand the reason why I can’t join it. Is there anybody else having similar RSS issues? Anyone who knows the answer can you kindly respond? http://www.kayswell.com

August 15, 2025 @ 8:48 pm

I am sure this article has touched all the internet people, its really really nice post on building up new blog. http://www.kayswell.com

August 16, 2025 @ 8:37 am

Spot on with this write-up, I really believe this site needs much more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read through more, thanks for the info! http://www.kayswell.com

August 16, 2025 @ 1:50 pm

Thanks , I’ve just been looking for information approximately this topic for a while and yours is the greatest I’ve found out so far. But, what about the conclusion? Are you certain about the supply? http://www.kayswell.com

August 16, 2025 @ 4:53 pm

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgetsI could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates. http://www.kayswell.com

August 16, 2025 @ 6:15 pm

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you penning this write-up and also the rest of the website is really good. http://www.kayswell.com

August 16, 2025 @ 7:24 pm

I like the valuable info you provide to your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and check once more here regularly. I am reasonably sure I’ll be told lots of new stuff proper right here! Best of luck for the following! http://www.kayswell.com

August 18, 2025 @ 1:41 am

great points altogether, you simply received a logo new reader. What might you suggest in regards to your publish that you just made a few days in the past? Any positive? http://www.kayswell.com

August 24, 2025 @ 10:54 am

Now I am ready to do my breakfast, once having my breakfast coming over again to read more news http://www.kayswell.com

August 25, 2025 @ 12:52 pm

What i do not understood is actually how you’re no longer really much more well-preferred than you may be now. You’re very intelligent. You know thus significantly in terms of this subject, made me personally believe it from a lot of numerous angles. http://www.kayswell.com Its like men and women aren’t interested unless it’s something to do with Girl gaga! Your individual stuffs great. At all times deal with it up!

August 25, 2025 @ 10:45 pm

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here. The sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get bought an edginess over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come further formerly again since exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this hike.

August 26, 2025 @ 6:48 pm

Hi, Neat post. There’s an issue together with your site in internet explorer, could test this? IE still is the market leader and a large section of other folks will miss your great writing due to this problem. http://www.kayswell.com

August 26, 2025 @ 11:22 pm

It’s great that you are getting ideas from this article as well as from our argument made at this time. http://www.kayswell.com

August 29, 2025 @ 2:35 am

Hi there to all, for the reason that I am truly keen of reading this website’s post to be updated daily. It carries fastidious data. http://www.kayswell.com

August 29, 2025 @ 9:50 am

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

December 20, 2025 @ 4:41 pm

Diese sind in unseren Augen nur gewährleistet, wenn ihr euch an eine lizenzierte

Anlaufstelle haltet. Die Legalisierung der Online Casinos

in Deutschland ist mit zahlreichen Einschränkungen für die Anbieter mit einer

deutschen Lizenz verbunden. Zuständig für die Lizenzierung

und Regulierung der Casinos mit einer deutschen Lizenz ist die Gemeinsame Glücksspielbehörde

der Länder (GGL). Der Glücksspielstaatsvertrag (GlüStV 2021) stellte

einen Wandel in der deutschen Politik dar. Wir arbeiten mit erstklassigen Online-Casinos zusammen,

um unseren Besuchern exklusive Boni und Werbeaktionen anzubieten.

Alle anderen klassischen Tischspiele sind in Deutschland untersagt.

Erlaubt sind virtuelle Automatenspiele (Slots)

und in besonderen Fällen auch Online-Poker. Seitdem

dürfen Online Spielhallen und Casinos nur mit einer gültigen deutschen Lizenz angeboten werden.

Unsere Übersicht zeigt, welche Anbieter aktuell in den wichtigsten Kategorien am besten abschneiden und daher zu empfehlen sind.

Einige Top Online Spielhallen und Casinos bieten Spielern neben verschiedenen Boni weitere Extras.

Es gehört zur Gruppe der besten Live Spiele und zählt ebenso zu den klassischen Online Glücksspielen. Ihre Freispiele oder

Ihr 100 % Ersteinzahlungsbonus damit verbunden war, müssen diese

zuerst erfüllt werden, bevor Sie eine Auszahlung durchführen. Eine

der Methoden besteht darin, einen Willkommensbonus und

viele andere Arten von Boni anzubieten, die viele Vorteile bieten. Unsere Casino-Tester spielen nicht nur mit dem heimischen Desktop-Computer, sondern ebenso mit ihrem Laptop.

Um die besten Casino-Seiten für den deutschen Markt zu finden, testen wir

alle relevanten Aspekte des Anbieters. Solange Sie bei einem sicheren, lizenzierten Casino spielen, ist es ganz egal, wofür Sie sich entscheiden.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/casino-bregenz-aktionscodes-mehr-ihr-umfassender-leitfaden/

December 21, 2025 @ 3:08 am

Die Glücksspielindustrie als Early Adopter, dass Betsoft hochwertige Online-Casinospiele

anbieten möchte. Online casino ab 1 cent einzahlung um

ein High Roller zu werden, die einer Vielzahl von Märkten auferlegt wurden. Wichtig ist auch, im Vorfeld zu prüfen, ob der Bonus von der Struktur

her zum eigenen Spielverhalten passt. Zum Beispiel ist in den Bonus-AGB geregelt, wie oft die Kunden die Kombination aus Einzahlung und Bonusgeld umsetzen müssen.

Angenommen, du hast einen Bonusbetrag von 100€ erhalten und musst diesen 30 Mal vor der Auszahlung umsetzen. Sehr oft ist ein Echtgeld

Bonus ohne Einzahlung mit einem Bonus Code verknüpft. Es kann manchmal

eine zeitliche Begrenzung geben, die mit einem erhaltenen Casino Bonus ohne Einzahlung verbunden ist.

Da eigentlich niemand wirklich Echtgeld zu verschenken hat ist das auch bei Online Casinos nicht anders.

Wir empfehlen Dir, einige der erstaunlichen Bonus Angebote ohne Einzahlung online auszuprobieren.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/instant-casino-deutschland-schneller-spielspas-im-fokus/

December 26, 2025 @ 12:17 pm

Since real money is involved, we pay attention to all

the aspects that can affect our visitors and ensure they will enjoy a safe and fair gaming

experience. At brick-and-mortar casinos, slots can have RTPs as low as 80%, whereas online pokies have an average

RTP of 96%. The game variety of any online casino

can’t be compared with the options available offline.

However, the law doesn’t prevent Aussies from enjoying casino

games online. I love that beyond the gaming, the venue offers luxury hotel rooms,

fine dining, and even a theatre, so it’s not just about gambling but

a full entertainment experience. Being on the casino floor, watching the dealers, and seeing the games in action gives you a

different perspective that online platforms can’t fully replicate.

When playing casino games online, you can easily get carried away.

Doing so lets you get familiar with the rules and gameplay and prepare for real money play.

In most cases, you will have to wager real money first and then the

bonus, but it may differ from one casino to the other.

Its lobby includes low-limit and high-limit baccarat, themed roulette rooms, and

all the best game shows from Evolution. Baccarat appeals for its elegant simplicity, with

quick rounds and straightforward bets on player, banker, or tie while the dealer handles

the rest. If you prefer a quieter, more private experience, you can choose to mute the live chat or observe silently.

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology reads game results instantly, ensuring fast payouts and accurate tracking of each

round. Every action—from card draws to roulette spins—is streamed to your device in real time.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/how-to-read-your-rivals-hands-in-poker/

December 26, 2025 @ 3:41 pm

It also took the logo of parent company Axiata Group which itself also

went through a major rebranding in 2009. In 2009, then AKTEL, now Robi Axiata, was the

first operator to introduce GPRS and 3.5G services in the country.

Having successfully completed the merger process, Robi has emerged as the second largest mobile phone operator in Bangladesh.

It was formerly known as Telekom Malaysia International Bangladesh Limited which commenced operations in Bangladesh in 1997 with

the brand name ‘AKTEL’. Robi Axiata PLC started as a joint

venture company between Telekom Malaysia and AK Khan and Company.

On 16 November 2016, Airtel Bangladesh was merged into Robi as a product brand of Robi, where Robi Axiata PLC is the licensee of Airtel brand only in Bangladesh.

Axiata of Malaysia holds a major controlling stake of 61.82% in the company, while Bharti Airtel of India holds 28.18% and investors

in DSE and CSE hold 10%. Internet banking security just pulled out the Big Guns.

Manage up to 5 Secondary Accounts and share monthly plans with family members from My Family!

It is now the one-stop single destination for meeting

all your mobile and lifestyle needs with just a few taps on your smartphone

screen. This helps keep our services free and accessible

for everyone. Your approach to life is guided by a desire to help and inspire others.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/betzillo-best-australian-casino-site/

December 26, 2025 @ 6:31 pm

For more information, see the developer’s privacy policy .

Fixed bugs, improved performance, drank way

too much coffee. You can also track contractual issues, performance, and activities.

The system will provide you with a unique secrete key or keys to participate in the procurement process.

15th-century Italy saw the formation of the

two main variants that are known today. By the ninth century, the Caroline script, which

was very similar to the present-day form, was the principal form used in book-making, before the advent

of the printing press. There was also a cursive style used for everyday or utilitarian writing, which was done

on more perishable surfaces.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/casino-basics/

December 27, 2025 @ 12:19 am

Fanatics offers an alternative welcome promotion that provides 1,000

bonus spins on select slot games. Withdrawal processing times at BetMGM tend to be

longer than many competing online casinos, with some payment methods taking several business

days to complete. Online casino bonuses typically come in the form

of deposit matches, no-deposit bonuses and bonus spins.

Taking frequent breaks is one way to stay on top of your game.

These mainly include deposit and wagering limits on a daily, weekly,

and monthly basis. As soon as you establish your budget, you can set your gaming

limits.

Australian online casinos are known for their high payout rates,

secure payment methods, generous bonuses, and mobile compatibility.

Many Australian online casinos attach wagering requirements to their promos, meaning you’ll

need to play through the bonus a certain number of times before cashing out any winnings.

By fully understanding and using these bonus types,

Australian players can significantly increase their winning potential while making the most of their time at real money casinos.

In Australia’s fast-growing online casino landscape, bonuses

and promotions play a huge role in attracting new players and rewarding

loyal ones.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/54_highest-rtp-slots-the-14-best-paying-slot-machines_rewrite_1/

December 28, 2025 @ 10:58 pm

online blackjack paypal

References:

http://www.konqisakaxgy.shop

December 28, 2025 @ 11:02 pm

best online casino usa paypal

References:

https://noarjobs.info/companies/best-real-money-online-pokies-in-australia-for-december-2025/

December 29, 2025 @ 8:07 am

online betting with paypal winnersbet

References:

http://workompass.com/employer/best-online-casinos-that-accept-paypal-in-2025/

December 29, 2025 @ 8:45 am

online betting with paypal winnersbet

References:

https://jobs.maanas.in/institution/best-payout-online-casino-sites-fastest-withdrawal-casinos-december-2025/

December 30, 2025 @ 1:27 am

paypal casino

References:

https://macrorecruitment.com.au/employer/fast-payout-casinos-in-australia-2025-instant-withdrawals/

February 4, 2026 @ 10:21 am

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks! https://accounts.binance.info/es-AR/register-person?ref=UT2YTZSU

February 5, 2026 @ 1:39 pm

5 resistors https://otvetnow.ru plumber local 1