Review: Plant Life (Mild Frenzy)

In a world where plants are the enemy, police-detective Priss must choose between her love for the illegal flower she owns, or the success of her murder investigation, in which her flower’s doppelgänger is the prime suspect. Where does her allegiance really lie?

Publisher: Mild Frenzy

Publisher: Mild Frenzy

Writer: Iqbal Ali

Artist: Priscilla Grippa, Ken Reynolds(Lettering)

Price: £8.99 from Amazon

Set in a futuristic, dystopian city, plants (or ‘creepers’) are deemed the enemy. To own or harbour a plant is a criminal offence. Detective Priss must often make the tough decision to incinerate (Plant Life’s version of the death sentence) creepers she’s arrested. However, unknown to the police, there exists a secret botanical garden outside of their metropolis, a place where plant-lovers can secretly grow their own plants, and chief detective Priss is hiding one heck of a secret there – her illegally grown flower, Ophreilda. As Priss struggles with her loyalty to the police force, and her love for Ophreilda, writer Iqbal Ali (x, y, z) creates a thin line between morality and immorality, and between healthy and toxic relationships.

As the rest of Plant Life is drawn in black and white, the colourful front cover gives the reader a more detailed glimpse into Priss’s world and does a great job at hinting at the ambiguity surrounding plants. Throughout Plant Life, plants are widely regarded as criminals; we are told that they kill and are slowly trying to take over the city. But in the botanical garden, humans seem totally at peace with plants, able to lie next to them, touch them, and rest in harmony. Grippa perfectly captures this ambiguity in the cover art: the flower manages to look both vibrant and sinister with its tentacle-like stigma, and the sleeping Priss manages to seem both peaceful and in danger lying next to it. We can subtly see a greying corner in the bottom-right of the cover, which is also suggestive of the plant’s ambiguity: is it giving life to Priss (represented by the illustration growing colourful), or is it sucking that life away (represented by the page slowly turning grey)? It is impossible to say either way, and Ali and Grippa do a great job of keeping this equivocal all the way through.

As the rest of Plant Life is drawn in black and white, the colourful front cover gives the reader a more detailed glimpse into Priss’s world and does a great job at hinting at the ambiguity surrounding plants. Throughout Plant Life, plants are widely regarded as criminals; we are told that they kill and are slowly trying to take over the city. But in the botanical garden, humans seem totally at peace with plants, able to lie next to them, touch them, and rest in harmony. Grippa perfectly captures this ambiguity in the cover art: the flower manages to look both vibrant and sinister with its tentacle-like stigma, and the sleeping Priss manages to seem both peaceful and in danger lying next to it. We can subtly see a greying corner in the bottom-right of the cover, which is also suggestive of the plant’s ambiguity: is it giving life to Priss (represented by the illustration growing colourful), or is it sucking that life away (represented by the page slowly turning grey)? It is impossible to say either way, and Ali and Grippa do a great job of keeping this equivocal all the way through.

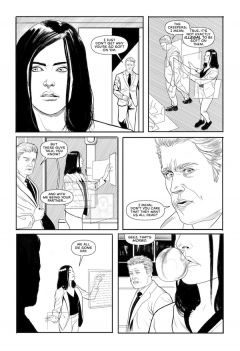

The art throughout the rest of the graphic novel is completely black and white but remains just as detailed. We open with a shot of people either passed out or sleeping on the ground, surrounded by plants who look like both predators and protectors. We really enjoyed the details Grippa put into her drawings of the plants: despite having no faces and therefore being expressionless, she manages to make them look incredibly sinister, almost as if they’re coiled back, ready to spring. Equally wonderful are her drawings of the dystopian metropolis outside of the botanical garden: the city is wasting away, quite literally decaying, as plants slowly slither and slide their way through cracks and crevices.

At less than one hundred pages, writer Ali manages to keep the pace quick and exciting throughout with his main plant vs human plot. Though this is much more of a futuristic, sci-fi-esque graphic novel than a murder mystery, it still manages to be gripping with its storyline and ambivalence. Because it’s so short, there is limited time to introduce many new characters, so the story is always focused on Priss and the people she briefly interacts with. Although it didn’t feel like the characters were glossed over (this is Priss’s narrative after all) it would be great to see another volume so that we could get some more background on the lady who owns the illegal botanical garden, or Priss’s snide colleague Eckhard.

At less than one hundred pages, writer Ali manages to keep the pace quick and exciting throughout with his main plant vs human plot. Though this is much more of a futuristic, sci-fi-esque graphic novel than a murder mystery, it still manages to be gripping with its storyline and ambivalence. Because it’s so short, there is limited time to introduce many new characters, so the story is always focused on Priss and the people she briefly interacts with. Although it didn’t feel like the characters were glossed over (this is Priss’s narrative after all) it would be great to see another volume so that we could get some more background on the lady who owns the illegal botanical garden, or Priss’s snide colleague Eckhard.

It’s hard to ignore the way in which people talk about plants throughout Plant Life: derogatorily naming them ‘creepers’ and automatically assuming crimes are done by plants seems to be a comment by Ali on modern-day racism, and how certain people can become ostracised from society because those with privilege choose to condemn and expel them (reminiscent of Jordan Peele’s Us). Ali could be hinting that the plants only act out in response to the treatment they’ve received from others. On the other side of the coin, the plants could represent addiction, and being unable to give up something you know is bad for you (as Priss struggles to leave her plant Ophreilda, which makes her life much more complicated). Being able to take multiple interpretations away from this graphic novel only adds to its effectiveness and importance.

The gift that keeps on giving, Plant Life includes some exciting bonus content at the back, including a full-colour cover gallery, and a small extra comic by Ali and Grippa. This is such an interesting and unique graphic novel, and we commend Ali on developing a bad-ass heroine like Priss in less than one hundred pages. We hope that Ali and Grippa will collaborate more in the future!

December 20, 2025 @ 5:43 am

Natürlich bieten wir auch Zugang zu dem Live Casino, in dem Sie

mit erfahrenen Dealern in Echtzeit im Livestream Roulette,

Poker, Baccarat und vieles mehr spielen können. Suchen Sie sich einfach einen unserer tausenden Slots aus und

spielen Sie los! Wir bieten Ihnen ein responsives Online Casino, in dem Sie auch unterwegs spielen können.

Haben Sie sich für ein Spiel entschieden, können Sie mit Echtgeld spielen und

so Gewinne generieren. Wenn Online Poker zu Ihren liebsten Spielen zählt,

werden Sie sich über die Auswahl an Pokerspielen im Mr Bet Casino freuen. Darüber hinaus können Sie in unserem Live Casino sogar gegen echte Dealer spielen. Bevorzugen Sie eher,

gegen einen echten Dealer zu spielen, sind unsere Live Casino Spiele

genau das Richtige für Sie!

Der Code ermöglicht Ihnen beispielsweise, bei der Einzahlung einen Bonus freizuschalten. Die Mr Bet Casino Bonus

Codes können Sie in Ihren E-Mails oder während

spezieller Aktionen erhalten. Außerdem spielt es eine Rolle,

ob Sie Ihr Spielerkonto verifizieren müssen.

December 27, 2025 @ 12:16 am

With its sleek glass tower and iconic presence, the complex redefines luxury in Australia.

Children are welcome in hotel areas, select restaurants, and general facilities.

Crown Sydney operates 24 hours a day for hotel guests and gaming members.

Crown Sydney offers premium spaces for executive meetings, corporate events, and private

receptions. Experience the stunning beauty of Sydney from above at the Crown Sky Deck,

an exclusive observation platform offering 360° views

of the Harbour Bridge, Opera House, and skyline. Crown Sydney offers

a premium selection of late-night spots, from exclusive cocktail lounges like Teahouse and 88 Noodle to vibrant social hubs like Cliq Bar.

A shortlist of designs from Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill, Kohn Pedersen Fox and WilkinsonEyre were subsequently selected and a jury

panel was formed to select the hotel’s final design and Principal Architect.

In 2013, Crown Resorts launched a design competition,

seeking expressions of interest from eight architecture firms with experience in similar hospitality focused projects.

Initial site works commenced in October 2016, starting with an excavation and decontamination of the site, mostly of remnants of asbestos; indicative of the site’s industrial history.

On 23 April 2024, the NSW Independent Casino Commission reinstated Crown Sydney’s unconditional casino licence.

Following a complete overhaul of Crown Resort’s board,

management and procedures, a conditional licence was finally granted for

the casino in June 2022, allowing for its opening in August 2022.

Despite the inability of the casino to open,

other operations within the Crown Sydney building were unaffected.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/top-welcome-bonuses-online-casinos/

December 27, 2025 @ 12:35 pm

Of course, game fairness and transparent terms and conditions should also be taken into consideration. We’ve got years of experience

and manual testing under our belts, which helps us distinguish legit from scammy

operators. Third-party testing by agencies like iTechLabs or eCOGRA is essential to prove

that the stated RTP is the actual RTP of the game. The minimum

deposit limit is A$20, while the maximum varies depending on the

method but is usually A$6,000. You can deposit using credit/debit cards, MiFinity, Neosurf, eZeeWallet,

Instant Bank Transfer, and crypto.

The experts view on the percentage fees and then give attention to those Australian gambling sites which pay more than 86%.

Examining recommendations is the greatest approach to search for suggestions on Australian gambling sites.

And after examine Terms & Conditions, make an advance payment, pick up good bonuses and so forth.

This is probably fine to play slots online and make

sure that you get large amount of cash.

Its popularity stems from the excitement, skill, and strategic thinking required to succeed

in this thrilling game of chance. If you have a blackjack strategy, you can improve

your chances of winning the game. Blackjack is a popular table game that requires a bit of skill

to win. Online pokies, also known as slots, are very popular in Australia.

Players ought to read the Ts & Cs thoroughly to understand what

to expect at the casino. To cash out your winnings, you must fulfill

the playthrough requirements.

December 29, 2025 @ 4:53 am

paypal casino

References:

https://externalliancerh.com/

December 29, 2025 @ 5:12 am

online casino real money paypal

References:

https://woodwell.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=101593

January 14, 2026 @ 10:31 am

To be honest, I needed Amoxicillin without waiting and came across Antibiotics Express. It allows you to purchase generics online legally. In case of a bacterial infection, check this shop. Overnight shipping guaranteed. Visit here: check here. Cheers.

January 14, 2026 @ 4:43 pm

Lately, I needed antibiotics fast and came across Antibiotics Express. You can order meds no script safely. For treating strep throat, this is the best place. Discreet packaging to USA. Check it out: website. Get well soon.

January 15, 2026 @ 10:59 am

п»їLately, I needed Doxycycline quickly and discovered a reliable pharmacy. You can order meds no script securely. For treating strep throat, this is the best place. Discreet packaging available. Visit here: safe antibiotics for purchase. Good luck.

January 17, 2026 @ 7:50 am

Merhaba arkadaşlar, ödeme yapan casino siteleri bulmak istiyorsanız, bu siteye mutlaka göz atın. Lisanslı firmaları ve fırsatları sizin için inceledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: kaçak bahis siteleri iyi kazançlar.

January 17, 2026 @ 8:45 am

Salamlar, əgər siz yaxşı kazino axtarırsınızsa, mütləq Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Canlı oyunlar və rahat pul çıxarışı burada mövcuddur. İndi qoşulun və ilk depozit bonusunu götürün. Sayta keçmək üçün link: https://pinupaz.jp.net/# Pin Up Azerbaijan uğurlar hər kəsə!

January 17, 2026 @ 10:25 am

Pin-Up AZ Azərbaycanda ən populyar kazino saytıdır. Burada minlərlə oyun və canlı dilerlər var. Qazancı kartınıza anında köçürürlər. Mobil tətbiqi də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Giriş linki https://pinupaz.jp.net/# ətraflı məlumat tövsiyə edirəm.

January 17, 2026 @ 10:56 am

Pin-Up AZ ölkəmizdə ən populyar kazino saytıdır. Saytda çoxlu slotlar və Aviator var. Qazancı kartınıza anında köçürürlər. Mobil tətbiqi də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Rəsmi sayt https://pinupaz.jp.net/# Pin-Up Casino yoxlayın.

January 17, 2026 @ 3:31 pm

Selamlar, sağlam casino siteleri arıyorsanız, bu siteye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve bonusları sizin için listeledik. Dolandırılmamak için doğru adres: türkçe casino siteleri bol şanslar.

January 17, 2026 @ 3:48 pm

2026 yılında en çok kazandıran casino siteleri hangileri? Cevabı platformumuzda mevcuttur. Bedava bahis veren siteleri ve yeni adres linklerini paylaşıyoruz. İncelemek için https://cassiteleri.us.org/# en iyi casino siteleri fırsatı kaçırmayın.

January 17, 2026 @ 4:30 pm

Selam, güvenilir casino siteleri bulmak istiyorsanız, hazırladığımız listeye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve bonusları sizin için inceledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: canlı casino siteleri iyi kazançlar.

January 17, 2026 @ 7:37 pm

Selam, güvenilir casino siteleri arıyorsanız, bu siteye kesinlikle göz atın. Lisanslı firmaları ve bonusları sizin için inceledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: güvenilir casino siteleri iyi kazançlar.

January 17, 2026 @ 9:39 pm

Selam, ödeme yapan casino siteleri arıyorsanız, hazırladığımız listeye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve fırsatları sizin için listeledik. Dolandırılmamak için doğru adres: güvenilir casino siteleri iyi kazançlar.

January 17, 2026 @ 11:51 pm

Situs Bonaslot adalah agen judi slot online terpercaya di Indonesia. Ribuan member sudah mendapatkan Maxwin sensasional disini. Proses depo WD super cepat kilat. Situs resmi п»їBonaslot daftar gas sekarang bosku.

January 18, 2026 @ 1:54 am

Bocoran slot gacor hari ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Situs ini anti rungkad dan aman. Promo menarik menanti anda. Akses link: п»їhttps://bonaslotind.us.com/# login sekarang dan menangkan.

January 18, 2026 @ 2:19 am

Pin Up Casino Azərbaycanda ən populyar platformadır. Burada minlərlə oyun və canlı dilerlər var. Qazancı kartınıza tez köçürürlər. Mobil tətbiqi də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Giriş linki https://pinupaz.jp.net/# ətraflı məlumat baxın.

January 18, 2026 @ 4:44 am

Pin-Up AZ ölkəmizdə ən populyar kazino saytıdır. Burada çoxlu slotlar və canlı dilerlər var. Qazancı kartınıza tez köçürürlər. Proqramı də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Rəsmi sayt Pin Up online baxın.

January 18, 2026 @ 7:48 am

Yeni Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtarırsınızsa, bura baxa bilərsiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə qeydiyyat olun və oynamağa başlayın. Xoş gəldin bonusu sizi gözləyir. Keçid: Pin Up yüklə hamıya bol şans.

January 18, 2026 @ 8:05 am

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, doğru yerdesiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə qeydiyyat olun və qazanmağa başlayın. Xoş gəldin bonusu sizi gözləyir. Keçid: pinupaz.jp.net uğurlar.

January 18, 2026 @ 12:51 pm

Selamlar, ödeme yapan casino siteleri bulmak istiyorsanız, bu siteye mutlaka göz atın. En iyi firmaları ve bonusları sizin için inceledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: mobil ödeme bahis iyi kazançlar.

January 18, 2026 @ 3:00 pm

2026 yılında en çok kazandıran casino siteleri hangileri? Cevabı platformumuzda mevcuttur. Deneme bonusu veren siteleri ve güncel giriş linklerini paylaşıyoruz. İncelemek için https://cassiteleri.us.org/# en iyi casino siteleri kazanmaya başlayın.

January 18, 2026 @ 3:52 pm

Canlı casino oynamak isteyenler için kılavuz niteliğinde bir site: https://cassiteleri.us.org/# kaçak bahis siteleri Hangi site güvenilir diye düşünmeyin. Editörlerimizin seçtiği bahis siteleri listesi ile sorunsuz oynayın. Tüm liste linkte.

January 18, 2026 @ 7:57 pm

Bocoran slot gacor hari ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Situs ini anti rungkad dan resmi. Promo menarik menanti anda. Akses link: https://bonaslotind.us.com/# Bonaslot link alternatif dan menangkan.

January 18, 2026 @ 7:57 pm

2026 yılında en çok kazandıran casino siteleri hangileri? Cevabı platformumuzda mevcuttur. Deneme bonusu veren siteleri ve yeni adres linklerini paylaşıyoruz. İncelemek için listeyi gör kazanmaya başlayın.

January 18, 2026 @ 9:55 pm

Merhaba arkadaşlar, sağlam casino siteleri arıyorsanız, hazırladığımız listeye kesinlikle göz atın. Lisanslı firmaları ve bonusları sizin için listeledik. Güvenli oyun için doğru adres: casino siteleri 2026 bol şanslar.

January 18, 2026 @ 10:04 pm

Salam Gacor, lagi nyari situs slot yang hoki? Coba main di Bonaslot. RTP Live tertinggi hari ini dan pasti bayar. Deposit bisa pakai Dana tanpa potongan. Login disini: Bonaslot slot salam jackpot.

January 18, 2026 @ 10:51 pm

Online slot oynamak isteyenler için rehber niteliğinde bir site: buraya tıkla Hangi site güvenilir diye düşünmeyin. Onaylı bahis siteleri listesi ile rahatça oynayın. Detaylar linkte.

January 19, 2026 @ 12:11 am

Salam Gacor, cari situs slot yang gacor? Coba main di Bonaslot. Winrate tertinggi hari ini dan pasti bayar. Isi saldo bisa pakai Dana tanpa potongan. Login disini: Bonaslot login semoga maxwin.

January 19, 2026 @ 12:16 am

Situs Bonaslot adalah bandar judi slot online terpercaya di Indonesia. Banyak member sudah mendapatkan Maxwin sensasional disini. Transaksi super cepat hanya hitungan menit. Situs resmi п»їlogin sekarang jangan sampai ketinggalan.

January 19, 2026 @ 3:08 am

Pin Up Casino Azərbaycanda ən populyar kazino saytıdır. Burada çoxlu slotlar və canlı dilerlər var. Pulu kartınıza anında köçürürlər. Mobil tətbiqi də var, telefondan oynamaq çox rahatdır. Giriş linki https://pinupaz.jp.net/# bura daxil olun yoxlayın.

January 19, 2026 @ 4:52 am

Info slot gacor hari ini: mainkan Gate of Olympus atau Mahjong Ways di Bonaslot. Situs ini anti rungkad dan resmi. Bonus new member menanti anda. Akses link: п»їbonaslotind.us.com dan menangkan.

January 19, 2026 @ 5:45 am

Bonaslot adalah agen judi slot online nomor 1 di Indonesia. Ribuan member sudah merasakan Maxwin sensasional disini. Transaksi super cepat hanya hitungan menit. Link alternatif п»їhttps://bonaslotind.us.com/# Bonaslot login gas sekarang bosku.

January 19, 2026 @ 11:07 am

Aktual Pin Up giriş ünvanını axtaranlar, doğru yerdesiniz. Bloklanmayan link vasitəsilə hesabınıza girin və qazanmağa başlayın. Pulsuz fırlanmalar sizi gözləyir. Keçid: sayta keçid uğurlar.

January 19, 2026 @ 12:00 pm

Salam dostlar, siz də yaxşı kazino axtarırsınızsa, mütləq Pin Up saytını yoxlayasınız. Yüksək əmsallar və sürətli ödənişlər burada mövcuddur. Qeydiyyatdan keçin və ilk depozit bonusunu götürün. Oynamaq üçün link: ətraflı məlumat uğurlar hər kəsə!

January 19, 2026 @ 3:38 pm

Hello, Lately discovered the best source from India for cheap meds. If you need medicines from India safely, this store is worth checking. They offer lowest prices to USA. More info here: indiapharm.in.net. Hope it helps.

January 19, 2026 @ 5:02 pm

Hey guys, Lately stumbled upon a useful source from India for affordable pills. If you need medicines from India without prescription, IndiaPharm is the best place. You get secure delivery to USA. More info here: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Hope it helps.

January 19, 2026 @ 9:11 pm

Hi, To be honest, I found a reliable online drugstore where you can buy pills hassle-free. For those who need safe pharmacy delivery, this site is very good. Fast delivery plus it is very affordable. See for yourself: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Thx.

January 19, 2026 @ 9:57 pm

Hey guys, I just stumbled upon a useful Indian pharmacy to buy generics. For those looking for generic pills cheaply, this store is the best place. You get secure delivery worldwide. Take a look: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Hope it helps.

January 20, 2026 @ 2:23 am

Hello, Lately stumbled upon the best Indian pharmacy to buy generics. For those looking for medicines from India at factory prices, this site is highly recommended. You get fast shipping to USA. Check it out: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Cheers.

January 20, 2026 @ 4:25 am

Hello, Lately found the best online drugstore to save on Rx. If you want to buy cheap antibiotics cheaply, IndiaPharm is very reliable. It has wholesale rates guaranteed. More info here: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Cheers.

January 20, 2026 @ 7:41 am

Hello everyone, Just now came across a reliable Mexican pharmacy for cheap meds. If you are tired of high prices and need cheap antibiotics, this store is the best option. No prescription needed plus very reliable. Check it out: buy meds from mexico. Cya.

January 20, 2026 @ 8:13 am

Hey guys, I just discovered a useful source from India for cheap meds. If you need cheap antibiotics without prescription, this store is the best place. They offer wholesale rates worldwide. More info here: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Good luck.

January 20, 2026 @ 3:08 pm

Hello everyone, Just now came across a great website for affordable pills. For those seeking and want affordable prescriptions, this site is the best option. No prescription needed and very reliable. Visit here: read more. I hope you find what you need.

January 20, 2026 @ 3:15 pm

To be honest, I recently came across an awesome website for cheap meds. If you want to save money and want cheap antibiotics, this site is a game changer. Fast shipping plus it is safe. Visit here: visit website. Appreciate it.

January 20, 2026 @ 6:16 pm

Greetings, I wanted to share a great online drugstore to order generics online. If you need cheap meds, this store is worth a look. They ship globally plus huge selection. Check it out: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Thx.

January 20, 2026 @ 10:15 pm

To be honest, I just discovered an amazing Indian pharmacy for cheap meds. For those looking for cheap antibiotics cheaply, IndiaPharm is worth checking. They offer fast shipping guaranteed. More info here: indiapharm.in.net. Hope it helps.

January 21, 2026 @ 12:19 am

Hey everyone, To be honest, I found a reliable online drugstore for purchasing medications securely. If you are looking for cheap meds, this site is highly recommended. They ship globally plus it is very affordable. Link here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Thanks!

January 21, 2026 @ 12:44 am

Hello, I just stumbled upon an amazing online drugstore to buy generics. If you need cheap antibiotics cheaply, this store is worth checking. They offer secure delivery to USA. More info here: this site. Good luck.

January 21, 2026 @ 5:19 am

Hey guys, Lately found an amazing online drugstore to save on Rx. If you want to buy cheap antibiotics safely, this store is the best place. It has wholesale rates worldwide. Visit here: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Best regards.

January 21, 2026 @ 5:30 am

Greetings, Lately discovered an awesome resource to save on Rx. If you are tired of high prices and need affordable prescriptions, this store is the best option. No prescription needed plus it is safe. Visit here: buy meds from mexico. Best wishes.

January 21, 2026 @ 6:02 am

Hey there, I recently discovered a great website for purchasing generics hassle-free. For those who need cheap meds, this store is worth a look. Great prices and it is very affordable. Link here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Best regards.

January 21, 2026 @ 7:47 am

Hi, To be honest, I found a reliable online drugstore where you can buy prescription drugs cheaply. If you are looking for safe pharmacy delivery, this site is highly recommended. They ship globally plus no script needed. Link here: Trust Pharmacy online. Hope this was useful.

January 21, 2026 @ 7:53 am

Hi guys, Lately came across a trusted online source for affordable pills. If you want to save money and need meds from Mexico, this store is a game changer. Great prices and secure. Take a look: this site. All the best.

January 21, 2026 @ 12:25 pm

Greetings, I recently found an awesome website to buy medication. For those seeking and want generic drugs, Pharm Mex is highly recommended. Fast shipping and very reliable. Check it out: https://pharm.mex.com/#. Hope this was useful.

January 21, 2026 @ 12:52 pm

Hello everyone, Lately discovered an awesome resource to buy medication. If you are tired of high prices and need affordable prescriptions, this site is the best option. Great prices plus very reliable. Take a look: https://pharm.mex.com/#. Cya.

January 21, 2026 @ 3:03 pm

Greetings, I just found the best source from India to buy generics. If you want to buy cheap antibiotics without prescription, IndiaPharm is worth checking. It has wholesale rates worldwide. Check it out: IndiaPharm. Best regards.

January 21, 2026 @ 4:41 pm

Greetings, I recently discovered a useful source for meds for purchasing generics securely. If you need cheap meds, this site is highly recommended. Secure shipping plus no script needed. Link here: https://onlinepharm.jp.net/#. Thank you.

January 21, 2026 @ 8:12 pm

Hey guys, Lately discovered an amazing source from India to buy generics. If you want to buy medicines from India safely, IndiaPharm is the best place. You get lowest prices worldwide. More info here: India Pharm Store. Cheers.

January 22, 2026 @ 12:00 am

To be honest, Just now came across an awesome online source for affordable pills. If you want to save money and need generic drugs, Pharm Mex is worth checking out. Fast shipping and very reliable. Visit here: https://pharm.mex.com/#. Best of luck.

January 22, 2026 @ 2:18 am

Hey guys, I just found a great website for cheap meds. For those looking for ED meds without prescription, this site is very reliable. It has wholesale rates guaranteed. More info here: https://indiapharm.in.net/#. Hope it helps.

January 22, 2026 @ 3:15 am

Hey guys, I just found the best source from India for affordable pills. If you want to buy medicines from India at factory prices, this store is very reliable. It has secure delivery to USA. Take a look: indiapharm.in.net. Good luck.

January 22, 2026 @ 4:59 am

Hey there, I just discovered a trusted resource for affordable pills. If you are tired of high prices and need affordable prescriptions, this site is highly recommended. Fast shipping plus very reliable. Visit here: pharm.mex.com. Take care.

January 22, 2026 @ 11:46 am

Dostlar selam, Vay Casino oyuncuları için önemli bir bilgilendirme paylaşıyorum. Malum site adresini tekrar değiştirdi. Giriş sorunu yaşıyorsanız panik yapmayın. Çalışan Vaycasino giriş adresi artık aşağıdadır: Resmi Site Paylaştığım bağlantı üzerinden vpn kullanmadan siteye erişebilirsiniz. Lisanslı bahis deneyimi sürdürmek için Vay Casino tercih edebilirsiniz. Herkese bol kazançlar dilerim.

January 22, 2026 @ 2:11 pm

Matbet giris adresi laz?msa dogru yerdesiniz. Sorunsuz icin t?kla: https://matbet.jp.net/# Yuksek oranlar burada. Gencler, Matbet bahis son linki belli oldu.

January 22, 2026 @ 3:11 pm

Arkadaslar, Grandpashabet Casino yeni adresi ac?kland?. Giremeyenler buradan devam edebilir https://grandpashabet.in.net/#

January 22, 2026 @ 3:13 pm

Grandpashabet güncel adresi arıyorsanız işte burada. Hızlı giriş yapmak için tıkla https://grandpashabet.in.net/# Deneme bonusu burada.

January 22, 2026 @ 9:42 pm

Grandpashabet giriş adresi lazımsa doğru yerdesiniz. Hızlı erişim için Grandpashabet Giriş Yüksek oranlar bu sitede.

January 23, 2026 @ 12:59 am

Herkese merhaba, Casibom oyuncular? icin k?sa bir paylas?m yapmak istiyorum. Herkesin bildigi uzere site giris linkini erisim k?s?tlamas? nedeniyle tekrar guncelledi. Erisim sorunu varsa dogru yerdesiniz. Yeni Casibom guncel giris linki art?k paylas?yorum Casibom Bu link ile vpn kullanmadan hesab?n?za baglanabilirsiniz. Ayr?ca kay?t olanlara sunulan hosgeldin bonusu f?rsatlar?n? da inceleyin. Lisansl? casino keyfi surdurmek icin Casibom dogru adres. Herkese bol sans dilerim.

January 23, 2026 @ 1:13 am

Arkadaslar selam, bu populer site kullan?c?lar? icin k?sa bir bilgilendirme yapmak istiyorum. Bildiginiz gibi Casibom domain adresini erisim k?s?tlamas? nedeniyle tekrar guncelledi. Siteye ulas?m sorunu varsa cozum burada. Resmi Casibom guncel giris linki su an asag?dad?r Casibom Guncel Giris Bu link ile vpn kullanmadan siteye girebilirsiniz. Ek olarak kay?t olanlara sunulan hosgeldin bonusu kampanyalar?n? da inceleyin. Guvenilir bahis keyfi icin Casibom tercih edebilirsiniz. Herkese bol sans dilerim.

January 23, 2026 @ 3:59 am

Herkese selam, Vay Casino oyuncuları için kısa bir bilgilendirme paylaşıyorum. Malum platform giriş linkini tekrar değiştirdi. Erişim sorunu varsa endişe etmeyin. Yeni Vay Casino giriş adresi artık aşağıdadır: Vaycasino Sorunsuz Giriş Paylaştığım bağlantı ile doğrudan siteye erişebilirsiniz. Güvenilir casino deneyimi için Vay Casino doğru adres. Tüm forum üyelerine bol şans dilerim.

January 23, 2026 @ 8:39 am

Gencler, Grandpashabet Casino son linki ac?kland?. Giremeyenler su linkten devam edebilir https://grandpashabet.in.net/#

January 23, 2026 @ 1:01 pm

Grandpasha guncel linki laz?msa dogru yerdesiniz. H?zl? giris yapmak icin https://grandpashabet.in.net/# Yuksek oranlar burada.

January 23, 2026 @ 3:25 pm

Gençler, Grandpashabet yeni adresi açıklandı. Adresi bulamayanlar buradan giriş yapabilir Grandpashabet Giriş

January 23, 2026 @ 5:34 pm

Grandpasha giriş linki lazımsa işte burada. Sorunsuz erişim için https://grandpashabet.in.net/# Yüksek oranlar burada.

January 24, 2026 @ 12:25 am

Gencler, Grandpashabet son linki belli oldu. Giremeyenler buradan giris yapabilir Grandpashabet Bonus

January 24, 2026 @ 3:33 am

Dostlar selam, Vay Casino oyuncuları için önemli bir duyuru yapmak istiyorum. Bildiğiniz gibi Vaycasino adresini yine güncelledi. Erişim hatası yaşıyorsanız panik yapmayın. Çalışan siteye erişim linki artık aşağıdadır: Vaycasino İndir Bu link ile direkt hesabınıza girebilirsiniz. Güvenilir bahis deneyimi için Vaycasino doğru adres. Tüm forum üyelerine bol kazançlar dilerim.

January 24, 2026 @ 5:01 am

Gencler, Grandpashabet yeni adresi ac?kland?. Giremeyenler buradan giris yapabilir https://grandpashabet.in.net/#

January 24, 2026 @ 10:01 am

Grandpasha giriş linki lazımsa işte burada. Hızlı giriş yapmak için https://grandpashabet.in.net/# Yüksek oranlar burada.

January 24, 2026 @ 10:47 am

Grandpashabet giriş adresi lazımsa işte burada. Hızlı erişim için Grandpashabet Apk Yüksek oranlar bu sitede.

January 24, 2026 @ 4:34 pm

Matbet giriş adresi arıyorsanız doğru yerdesiniz. Hızlı için tıkla: Matbet Güvenilir mi Canlı maçlar bu sitede. Arkadaşlar, Matbet bahis yeni adresi belli oldu.

January 24, 2026 @ 8:56 pm

Arkadaslar selam, Casibom sitesi uyeleri ad?na onemli bir bilgilendirme paylas?yorum. Herkesin bildigi uzere bahis platformu giris linkini BTK engeli yuzunden tekrar guncelledi. Siteye ulas?m problemi cekenler icin link asag?da. Yeni siteye erisim baglant?s? art?k paylas?yorum Casibom Indir Bu link ile direkt siteye girebilirsiniz. Ek olarak yeni uyelere verilen hosgeldin bonusu kampanyalar?n? da inceleyin. En iyi slot deneyimi surdurmek icin Casibom dogru adres. Herkese bol kazanclar dilerim.

January 24, 2026 @ 9:07 pm

Dostlar selam, bu populer site oyuncular? icin onemli bir duyuru yapmak istiyorum. Bildiginiz gibi Casibom adresini BTK engeli yuzunden yine degistirdi. Giris sorunu cekenler icin cozum burada. Yeni Casibom guncel giris baglant?s? art?k asag?dad?r Casibom Yeni Adres Bu link uzerinden dogrudan siteye girebilirsiniz. Ek olarak yeni uyelere sunulan hosgeldin bonusu kampanyalar?n? mutlaka inceleyin. Lisansl? bahis keyfi surdurmek icin Casibom tercih edebilirsiniz. Herkese bol sans dilerim.

January 24, 2026 @ 11:47 pm

Herkese merhaba, bu popüler site üyeleri için kısa bir duyuru yapmak istiyorum. Herkesin bildiği üzere site giriş linkini erişim kısıtlaması nedeniyle tekrar güncelledi. Giriş hatası çekenler için doğru yerdesiniz. Resmi Casibom güncel giriş bağlantısı şu an paylaşıyorum Casibom Bu link ile doğrudan siteye erişebilirsiniz. Ek olarak kayıt olanlara verilen freespin kampanyalarını da kaçırmayın. Güvenilir casino keyfi için Casibom tercih edebilirsiniz. Herkese bol kazançlar dilerim.

January 25, 2026 @ 3:46 am

Arkadaslar selam, Casibom sitesi uyeleri icin onemli bir duyuru yapmak istiyorum. Herkesin bildigi uzere bahis platformu adresini erisim k?s?tlamas? nedeniyle yine guncelledi. Erisim hatas? varsa link asag?da. Guncel Casibom guncel giris adresi art?k paylas?yorum https://casibom.mex.com/# Paylast?g?m baglant? uzerinden vpn kullanmadan hesab?n?za erisebilirsiniz. Ek olarak kay?t olanlara sunulan freespin kampanyalar?n? mutlaka kac?rmay?n. Guvenilir bahis deneyimi surdurmek icin Casibom dogru adres. Herkese bol kazanclar dilerim.

January 25, 2026 @ 5:40 am

Arkadaşlar, Grandpashabet Casino yeni adresi açıklandı. Giremeyenler buradan devam edebilir Grandpasha Giriş

January 25, 2026 @ 6:19 am

Grandpashabet güncel linki arıyorsanız doğru yerdesiniz. Hızlı giriş yapmak için Grandpashabet Sorunsuz Giriş Deneme bonusu burada.

January 25, 2026 @ 12:27 pm

Dostlar selam, Vaycasino oyuncuları için kısa bir bilgilendirme paylaşıyorum. Bildiğiniz gibi platform adresini tekrar değiştirdi. Erişim sorunu yaşıyorsanız endişe etmeyin. Çalışan Vaycasino giriş adresi artık aşağıdadır: Vaycasino Mobil Paylaştığım bağlantı üzerinden direkt siteye erişebilirsiniz. Lisanslı bahis deneyimi için Vay Casino doğru adres. Herkese bol kazançlar dilerim.

January 25, 2026 @ 1:01 pm

Arkadaslar, Grandpashabet son linki ac?kland?. Giremeyenler buradan giris yapabilir Grandpashabet Uyelik

January 25, 2026 @ 6:52 pm

Gençler, Grandpashabet son linki açıklandı. Giremeyenler buradan giriş yapabilir https://grandpashabet.in.net/#

January 25, 2026 @ 11:28 pm

Arkadaslar selam, Vaycasino oyuncular? icin onemli bir duyuru yapmak istiyorum. Bildiginiz gibi site giris linkini yine degistirdi. Giris hatas? yas?yorsan?z panik yapmay?n. Guncel siteye erisim adresi art?k asag?dad?r: https://vaycasino.us.com/# Bu link uzerinden direkt hesab?n?za girebilirsiniz. Guvenilir casino keyfi icin Vaycasino dogru adres. Herkese bol sans dilerim.

January 26, 2026 @ 1:11 am

Grandpasha güncel adresi arıyorsanız doğru yerdesiniz. Hızlı erişim için tıkla Siteye Git Deneme bonusu burada.

January 26, 2026 @ 5:02 am

Dostlar selam, Vay Casino oyuncular? ad?na onemli bir bilgilendirme yapmak istiyorum. Bildiginiz gibi platform giris linkini tekrar guncelledi. Giris hatas? varsa panik yapmay?n. Son Vaycasino giris linki su an asag?dad?r: Vay Casino Bu link uzerinden dogrudan siteye girebilirsiniz. Guvenilir bahis deneyimi surdurmek icin Vay Casino tercih edebilirsiniz. Herkese bol sans dilerim.

January 26, 2026 @ 6:07 am

Grandpashabet giris linki laz?msa iste burada. H?zl? giris yapmak icin Grandpashabet Kay?t Yuksek oranlar burada.

January 26, 2026 @ 12:22 pm

Chao c? nha, ai dang tim ch? n?p rut nhanh d? g? g?c Game bai thi vao ngay ch? nay. N?p rut 1-1: https://pacebhadrak.org.in/#. V? b? thanh cong.

January 26, 2026 @ 4:06 pm

Chào anh em, người anh em nào cần chỗ nạp rút nhanh để chơi Casino đừng bỏ qua con hàng này. Không lo lừa đảo: https://pacebhadrak.org.in/#. Chúc các bác rực rỡ.

January 26, 2026 @ 6:03 pm

Chao c? nha, bac nao mu?n tim c?ng game khong b? ch?n d? cay cu?c Da Ga thi vao ngay trang nay nhe. Uy tin luon: https://gramodayalawcollege.org.in/#. V? b? thanh cong.

January 26, 2026 @ 6:26 pm

Chào anh em, người anh em nào cần trang chơi xanh chín để cày cuốc Tài Xỉu đừng bỏ qua con hàng này. Không lo lừa đảo: Sunwin web. Về bờ thành công.

January 26, 2026 @ 9:50 pm

Hi các bác, người anh em nào cần chỗ nạp rút nhanh để cày cuốc Nổ Hũ thì xem thử địa chỉ này. Uy tín luôn: sunwin. Chúc các bác rực rỡ.

January 26, 2026 @ 10:15 pm

Hi cac bac, ai dang tim c?ng game khong b? ch?n d? choi Da Ga thi vao ngay trang nay nhe. Uy tin luon: Link vao Dola789. Hup l?c d?y nha.

January 27, 2026 @ 3:10 am

Xin chào 500 anh em, ai đang tìm trang chơi xanh chín để giải trí Casino đừng bỏ qua trang này nhé. Nạp rút 1-1: Link không bị chặn. Chiến thắng nhé.

January 27, 2026 @ 3:26 am

Chào cả nhà, bác nào muốn tìm nhà cái uy tín để cày cuốc Nổ Hũ đừng bỏ qua trang này nhé. Đang có khuyến mãi: https://pacebhadrak.org.in/#. Chiến thắng nhé.

January 27, 2026 @ 9:05 am

Hi cac bac, ngu?i anh em nao c?n trang choi xanh chin d? gi?i tri Tai X?u thi xem th? ch? nay. Uy tin luon: https://homemaker.org.in/#. Chi?n th?ng nhe.

January 27, 2026 @ 10:03 am

Xin chào 500 anh em, ai đang tìm chỗ nạp rút nhanh để gỡ gạc Đá Gà thì tham khảo địa chỉ này. Tốc độ bàn thờ: Link không bị chặn. Chúc các bác rực rỡ.

January 27, 2026 @ 12:45 pm

Hello mọi người, bác nào muốn tìm trang chơi xanh chín để giải trí Game bài đừng bỏ qua con hàng này. Đang có khuyến mãi: Tải Sunwin. Chúc các bác rực rỡ.

January 27, 2026 @ 4:18 pm

Hello mọi người, người anh em nào cần nhà cái uy tín để chơi Game bài đừng bỏ qua trang này nhé. Tốc độ bàn thờ: Game bài đổi thưởng. Về bờ thành công.

January 27, 2026 @ 5:04 pm

Hello mọi người, bác nào muốn tìm cổng game không bị chặn để gỡ gạc Tài Xỉu đừng bỏ qua chỗ này. Không lo lừa đảo: https://gramodayalawcollege.org.in/#. Húp lộc đầy nhà.

January 27, 2026 @ 7:59 pm

Chao anh em, ngu?i anh em nao c?n c?ng game khong b? ch?n d? choi Game bai thi xem th? con hang nay. N?p rut 1-1: https://gramodayalawcollege.org.in/#. Hup l?c d?y nha.

January 27, 2026 @ 10:15 pm

Chao anh em, bac nao mu?n tim san choi d?ng c?p d? cay cu?c Casino d?ng b? qua con hang nay. N?p rut 1-1: Nha cai BJ88. V? b? thanh cong.

January 27, 2026 @ 10:48 pm

Xin chào 500 anh em, nếu anh em đang kiếm cổng game không bị chặn để chơi Nổ Hũ thì vào ngay chỗ này. Tốc độ bàn thờ: https://pacebhadrak.org.in/#. Chiến thắng nhé.

January 28, 2026 @ 12:08 am

Chào anh em, người anh em nào cần cổng game không bị chặn để gỡ gạc Đá Gà thì tham khảo con hàng này. Tốc độ bàn thờ: Game bài đổi thưởng. Chúc anh em may mắn.

January 28, 2026 @ 7:12 am

Chào anh em, ai đang tìm trang chơi xanh chín để gỡ gạc Đá Gà thì vào ngay trang này nhé. Đang có khuyến mãi: https://homemaker.org.in/#. Chúc các bác rực rỡ.

January 28, 2026 @ 8:53 am

Hi các bác, nếu anh em đang kiếm cổng game không bị chặn để gỡ gạc Casino thì tham khảo địa chỉ này. Nạp rút 1-1: Đăng nhập BJ88. Chiến thắng nhé.

January 28, 2026 @ 11:27 am

Chao c? nha, ai dang tim trang choi xanh chin d? choi Casino d?ng b? qua con hang nay. Uy tin luon: https://homemaker.org.in/#. Chi?n th?ng nhe.

January 28, 2026 @ 11:29 am

Chào anh em, ai đang tìm nhà cái uy tín để giải trí Game bài đừng bỏ qua trang này nhé. Không lo lừa đảo: https://pacebhadrak.org.in/#. Chúc anh em may mắn.

January 28, 2026 @ 2:36 pm

Hi các bác, nếu anh em đang kiếm trang chơi xanh chín để chơi Đá Gà đừng bỏ qua chỗ này. Không lo lừa đảo: https://homemaker.org.in/#. Húp lộc đầy nhà.

January 28, 2026 @ 6:11 pm

Hello m?i ngu?i, ngu?i anh em nao c?n ch? n?p rut nhanh d? gi?i tri Da Ga thi tham kh?o d?a ch? nay. T?c d? ban th?: Game bai d?i thu?ng. V? b? thanh cong.

January 28, 2026 @ 9:59 pm

Hi các bác, nếu anh em đang kiếm trang chơi xanh chín để gỡ gạc Game bài đừng bỏ qua trang này nhé. Nạp rút 1-1: Link tải Sunwin. Húp lộc đầy nhà.

January 29, 2026 @ 2:49 am

Xin chao 500 anh em, ai dang tim san choi d?ng c?p d? gi?i tri Casino d?ng b? qua con hang nay. N?p rut 1-1: Link vao Dola789. Chi?n th?ng nhe.

January 29, 2026 @ 5:57 am

Hi các bác, người anh em nào cần cổng game không bị chặn để cày cuốc Nổ Hũ đừng bỏ qua chỗ này. Không lo lừa đảo: sunwin. Chiến thắng nhé.

January 29, 2026 @ 6:52 am

Chao c? nha, bac nao mu?n tim c?ng game khong b? ch?n d? cay cu?c Casino d?ng b? qua ch? nay. Khong lo l?a d?o: https://gramodayalawcollege.org.in/#. Chi?n th?ng nhe.

January 29, 2026 @ 11:34 am

https://fertilitypctguide.us.com/# how to get cheap clomid pills

January 29, 2026 @ 12:28 pm

Follicle Insight: cost cheap propecia – Follicle Insight

January 29, 2026 @ 3:21 pm

ivermectin 3 mg tablet dosage stromectol 3mg cost ivermectin buy australia

January 29, 2026 @ 5:28 pm

clomid: where to buy generic clomid prices – fertility pct guide

January 29, 2026 @ 9:13 pm

https://follicle.us.com/# buying generic propecia pill

January 29, 2026 @ 11:14 pm

AmiTrip: Elavil – AmiTrip Relief Store

January 30, 2026 @ 1:38 am

Iver Protocols Guide buy stromectol online Iver Protocols Guide

January 30, 2026 @ 1:53 am

https://iver.us.com/# ivermectin syrup

January 30, 2026 @ 5:35 am

Follicle Insight: Follicle Insight – buying generic propecia without insurance

January 30, 2026 @ 12:49 pm

Iver Protocols Guide: Iver Protocols Guide – ivermectin for sale

January 30, 2026 @ 4:09 pm

Follicle Insight generic propecia price propecia online

January 30, 2026 @ 7:41 pm

https://amitrip.us.com/# AmiTrip

January 30, 2026 @ 9:03 pm

https://fertilitypctguide.us.com/# how to get cheap clomid for sale

January 31, 2026 @ 3:18 am

Elavil: AmiTrip Relief Store – AmiTrip Relief Store

January 31, 2026 @ 3:47 am

https://iver.us.com/# ivermectin price usa

January 31, 2026 @ 7:00 am

AmiTrip Relief Store Generic Elavil Generic Elavil

January 31, 2026 @ 10:26 am

https://follicle.us.com/# propecia tablet

January 31, 2026 @ 1:25 pm

Amitriptyline: Elavil – Generic Elavil

January 31, 2026 @ 4:32 pm

https://amitrip.us.com/# buy Elavil

January 31, 2026 @ 5:02 pm

Generic Elavil: Generic Elavil – AmiTrip

January 31, 2026 @ 10:12 pm

fertility pct guide fertility pct guide fertility pct guide

January 31, 2026 @ 11:34 pm

https://follicle.us.com/# propecia brand name

January 31, 2026 @ 11:39 pm

get generic propecia online: Follicle Insight – generic propecia prices

February 1, 2026 @ 1:56 am

AmiTrip: Generic Elavil – AmiTrip

February 1, 2026 @ 5:51 am

https://follicle.us.com/# Follicle Insight

February 1, 2026 @ 6:01 am

Iver Protocols Guide: buy stromectol canada – Iver Protocols Guide

February 1, 2026 @ 9:31 am

Follicle Insight: buy propecia prices – Follicle Insight

February 1, 2026 @ 11:21 am

https://fertilitypctguide.us.com/# generic clomid for sale

February 1, 2026 @ 12:00 pm

https://fertilitypctguide.us.com/# fertility pct guide

February 1, 2026 @ 12:43 pm

cheap propecia prices: propecia sale – Follicle Insight

February 1, 2026 @ 1:22 pm

AmiTrip AmiTrip Relief Store AmiTrip

February 1, 2026 @ 4:20 pm

Iver Protocols Guide: ivermectin for humans – Iver Protocols Guide

February 1, 2026 @ 7:55 pm

Amitriptyline: Generic Elavil – Generic Elavil

February 1, 2026 @ 11:13 pm

buy Elavil: Generic Elavil – Generic Elavil

February 2, 2026 @ 3:38 am

Greetings, if you are looking for a trusted online pharmacy to order prescription drugs online. Check out MagMaxHealth: allopurinol. Selling high quality drugs and huge discounts. Thanks.

February 2, 2026 @ 4:36 am

To understand the proper usage instructions, please review the medical directory at: https://magmaxhealth.com/ for risk management.

February 2, 2026 @ 5:05 am

Greetings, if anyone needs detailed information on common medicines, I recommend this health wiki. It explains drug interactions in detail. Source: https://magmaxhealth.com/Naltrexone. Good info.

February 2, 2026 @ 8:35 am

Hey everyone, if you need a trusted drugstore to purchase medicines cheaply. I found MagMaxHealth: rosuvastatin. Stocking a wide range of meds and huge discounts. Thanks.

February 2, 2026 @ 10:09 am

Hi, if you are looking for side effects info about health treatments, I found this online directory. You can read about safety protocols clearly. Source: https://magmaxhealth.com/Rosuvastatin. Very informative.

February 2, 2026 @ 10:25 am

To start saving, I recommend this top-rated pharmacy pharmacy online usa for fast USA shipping. Take control of your health safely.

February 2, 2026 @ 1:14 pm

Hi guys, anyone searching for an affordable health store to buy pills securely. Check out this pharmacy: olanzapine. Selling a wide range of meds with fast shipping. Thanks.

February 2, 2026 @ 2:05 pm

Hi, if anyone needs dosage instructions on health treatments, check out this health wiki. You can read about drug interactions clearly. Reference: https://magmaxhealth.com/Clarinex. Thanks.

February 2, 2026 @ 2:57 pm

In terms of dosage guidelines, you can consult the medical directory at: https://magmaxhealth.com/clomid.html which covers risk management.

February 2, 2026 @ 6:43 pm

Hello, I wanted to share a reliable online pharmacy to buy health products cheaply. Take a look at this pharmacy: protonix. Selling generic tablets with fast shipping. Thanks.

February 2, 2026 @ 7:04 pm

Hi, if anyone needs a useful article about various medications, I recommend this medical reference. You can read about safety protocols in detail. Source: https://magmaxhealth.com/Celebrex. Very informative.

February 2, 2026 @ 8:31 pm

Hi all, if you are looking for dosage instructions about prescription drugs, I recommend this health wiki. It explains usage and risks clearly. See details: https://magmaxhealth.com/Olanzapine. Very informative.

February 3, 2026 @ 3:03 am

Greetings, if you are looking for detailed information on various medications, I recommend this medical reference. You can read about safety protocols in detail. See details: https://magmaxhealth.com/Methotrexate. Thanks.

February 3, 2026 @ 4:44 am

Hello, I recently found side effects info regarding common medicines, I found this online directory. It explains safety protocols very well. See details: https://magmaxhealth.com/Naltrexone. Hope this is useful.

February 3, 2026 @ 5:59 am

In terms of medical specifications, data is available at this resource: https://magmaxhealth.com/clarinex.html which covers safe treatment.

February 3, 2026 @ 8:34 am

Hi, for those searching for detailed information on common medicines, check out this useful resource. It covers safety protocols clearly. Link: https://magmaxhealth.com/Naltrexone. Good info.

February 3, 2026 @ 1:40 pm

tizanidine hydrochloride: Spasm Relief Protocols – muscle relaxer tizanidine

February 3, 2026 @ 6:28 pm

zofran side effects Nausea Care US ondansetron

February 3, 2026 @ 7:18 pm

muscle relaxer tizanidine: Spasm Relief Protocols – methocarbamol robaxin

February 3, 2026 @ 8:50 pm

http://spasmreliefprotocols.com/# otc muscle relaxer

February 4, 2026 @ 12:59 am

http://nauseacareus.com/# Nausea Care US

February 4, 2026 @ 1:03 am

Gastro Health Monitor: prilosec otc – generic prilosec

February 4, 2026 @ 3:39 am

Gastro Health Monitor: Gastro Health Monitor – Gastro Health Monitor

February 4, 2026 @ 5:37 am

prilosec medication prilosec side effects Gastro Health Monitor

February 4, 2026 @ 5:51 am

https://spasmreliefprotocols.com/# buy tizanidine without prescription

February 4, 2026 @ 1:55 pm

prilosec omeprazole: prilosec dosage – buy prilosec

February 4, 2026 @ 7:02 pm

buy tizanidine without prescription: Spasm Relief Protocols – tizanidine generic

February 4, 2026 @ 7:06 pm

Gastro Health Monitor Gastro Health Monitor omeprazole otc

February 4, 2026 @ 10:16 pm

https://spasmreliefprotocols.com/# tizanidine generic

February 5, 2026 @ 3:17 am

buy methocarbamol: otc muscle relaxer – methocarbamol medication

February 5, 2026 @ 9:22 am

Gastro Health Monitor prilosec medication Gastro Health Monitor

February 5, 2026 @ 9:41 am

over the counter muscle relaxers that work: Spasm Relief Protocols – antispasmodic medication

February 5, 2026 @ 1:47 pm

http://gastrohealthmonitor.com/# prilosec medication

February 5, 2026 @ 3:26 pm

Gastro Health Monitor: prilosec otc – omeprazole otc

February 5, 2026 @ 7:07 pm

https://spasmreliefprotocols.com/# zanaflex

February 5, 2026 @ 9:19 pm

Nausea Care US: Nausea Care US – Nausea Care US

February 5, 2026 @ 11:43 pm

muscle relaxer tizanidine muscle relaxant drugs muscle relaxers for back pain

February 5, 2026 @ 11:52 pm

https://gastrohealthmonitor.com/# Gastro Health Monitor

February 6, 2026 @ 4:53 am

https://spasmreliefprotocols.shop/# п»їbest muscle relaxer

February 6, 2026 @ 9:28 am

https://usmedsoutlet.shop/# US Meds Outlet

February 6, 2026 @ 9:32 am

otc muscle relaxer: Spasm Relief Protocols – tizanidine generic

February 6, 2026 @ 11:01 am

https://bajameddirect.com/# BajaMed Direct

February 6, 2026 @ 11:37 am

US Meds Outlet pharmacy prices canadian pharmacy world

February 6, 2026 @ 2:24 pm

http://bajameddirect.com/# prescriptions from mexico

February 6, 2026 @ 2:52 pm

online mexican pharmacies: mexico pharmacy – BajaMed Direct

February 6, 2026 @ 5:08 pm

https://indogenericexport.shop/# world pharmacy india

February 6, 2026 @ 8:18 pm

usa pharmacy: rx pharmacy – canadian pharmacy 365

February 6, 2026 @ 9:18 pm

online mexico pharmacy BajaMed Direct BajaMed Direct

February 6, 2026 @ 11:04 pm

https://bajameddirect.com/# mexican pharmacy menu

February 7, 2026 @ 1:40 am

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: Indo-Generic Export – indianpharmacy com

February 7, 2026 @ 7:24 am

top online pharmacy india: Indo-Generic Export – Online medicine home delivery

February 7, 2026 @ 8:06 am

https://bajameddirect.shop/# BajaMed Direct

February 7, 2026 @ 8:27 am

US Meds Outlet US Meds Outlet best rogue online pharmacy

February 7, 2026 @ 12:58 pm

https://indogenericexport.com/# otc muscle relaxer

February 7, 2026 @ 1:17 pm

mexi pharmacy: BajaMed Direct – pharma mexicana

February 7, 2026 @ 2:45 pm

https://indogenericexport.com/# zanaflex

February 7, 2026 @ 4:56 pm

indian pharmacy online: Online medicine home delivery – reputable indian pharmacies

February 7, 2026 @ 5:40 pm

https://usmedsoutlet.com/# online pharmacy usa

February 7, 2026 @ 7:47 pm

order medicine from mexico: BajaMed Direct – is mexipharmacy legit

February 8, 2026 @ 12:45 am

indian pharmacy top online pharmacy india top 10 pharmacies in india

February 8, 2026 @ 1:28 am

best online pharmacy india: Indo-Generic Export – top online pharmacy india

February 8, 2026 @ 4:16 am

list of online pharmacies: reliable canadian pharmacy – US Meds Outlet

February 8, 2026 @ 7:48 am

https://indogenericexport.shop/# robaxin generic

February 8, 2026 @ 8:37 am

buy prescription drugs from india india pharmacy india online pharmacy

February 8, 2026 @ 3:22 pm

mexican pharmacy las vegas: farmacia pharmacy mexico – online pharmacy in mexico

February 8, 2026 @ 4:44 pm

https://bajameddirect.com/# BajaMed Direct

February 8, 2026 @ 6:35 pm

BajaMed Direct: prescriptions from mexico – pharmacy in mexico online

February 8, 2026 @ 11:13 pm

BajaMed Direct: mexican medicine – mexican meds

February 9, 2026 @ 1:55 am

https://indogenericexport.com/# muscle relaxant drugs

February 9, 2026 @ 4:20 am

US Meds Outlet: US Meds Outlet – canadian world pharmacy

February 9, 2026 @ 4:23 am

medication from mexico: BajaMed Direct – BajaMed Direct

February 9, 2026 @ 5:09 am

https://usmedsoutlet.com/# canadadrugpharmacy com

February 9, 2026 @ 7:55 am

http://indogenericexport.com/# indian pharmacy online

February 9, 2026 @ 1:05 pm

https://usmedsoutlet.shop/# US Meds Outlet

February 9, 2026 @ 1:51 pm

Online medicine home delivery: Online medicine home delivery – indianpharmacy com

February 9, 2026 @ 3:47 pm

BajaMed Direct BajaMed Direct BajaMed Direct

February 9, 2026 @ 4:55 pm

BajaMed Direct: BajaMed Direct – online mexican pharmacies

February 9, 2026 @ 7:18 pm

indian pharmacy: Indo-Generic Export – indianpharmacy com

February 9, 2026 @ 7:58 pm

pharmacy website india: Indo-Generic Export – pharmacy website india

February 9, 2026 @ 11:01 pm

BajaMed Direct: BajaMed Direct – meds from mexico

February 9, 2026 @ 11:10 pm

BajaMed Direct pharmacy in mexico BajaMed Direct

February 9, 2026 @ 11:43 pm

https://bajameddirect.com/# BajaMed Direct

February 10, 2026 @ 12:10 am

discount pharmacy: canadian online pharmacy no prescription – US Meds Outlet

February 10, 2026 @ 5:01 am

BajaMed Direct: can i buy meds from mexico online – BajaMed Direct

February 10, 2026 @ 6:30 am

BajaMed Direct BajaMed Direct BajaMed Direct

February 10, 2026 @ 9:50 am

http://sertralineusa.com/# zoloft pill

February 10, 2026 @ 11:29 am

Iver Therapeutics: buy stromectol uk – ivermectin where to buy for humans

February 10, 2026 @ 12:28 pm

http://ivertherapeutics.com/# cost of stromectol medication

February 10, 2026 @ 1:48 pm

Iver Therapeutics: buy liquid ivermectin – generic ivermectin for humans

February 10, 2026 @ 2:14 pm

https://ivertherapeutics.com/# stromectol ivermectin tablets

February 10, 2026 @ 2:40 pm

buy zoloft: sertraline zoloft – zoloft medication

February 10, 2026 @ 3:09 pm

https://sertralineusa.com/# generic zoloft

February 10, 2026 @ 5:49 pm

zoloft pill: generic zoloft – zoloft medication

February 10, 2026 @ 7:19 pm

https://neuroreliefusa.shop/# Neuro Relief USA

February 10, 2026 @ 8:31 pm

https://smartgenrxusa.com/# online pharmacy pain medicine

February 10, 2026 @ 8:59 pm

zoloft no prescription: zoloft pill – zoloft pill

February 11, 2026 @ 12:09 am

neurontin 300 mg mexico: neurontin cost australia – Neuro Relief USA

February 11, 2026 @ 1:43 am

https://neuroreliefusa.com/# gabapentin

February 11, 2026 @ 1:57 am

how much is ivermectin: Iver Therapeutics – Iver Therapeutics

February 11, 2026 @ 3:14 am

Neuro Relief USA: drug neurontin 200 mg – cost of neurontin 600mg

February 11, 2026 @ 5:17 am

https://smartgenrxusa.com/# Smart GenRx USA

February 11, 2026 @ 6:27 am

Iver Therapeutics: Iver Therapeutics – Iver Therapeutics

February 11, 2026 @ 8:35 am

http://neuroreliefusa.com/# Neuro Relief USA

February 11, 2026 @ 9:47 am

neurontin 400 mg capsule: Neuro Relief USA – neurontin online usa

February 11, 2026 @ 11:39 am

Neuro Relief USA: Neuro Relief USA – Neuro Relief USA

February 11, 2026 @ 11:52 am

https://ivertherapeutics.shop/# ivermectin 4

February 11, 2026 @ 4:27 pm

Neuro Relief USA: neurontin 100mg price – neurontin mexico

February 11, 2026 @ 4:52 pm

Smart GenRx USA: Smart GenRx USA – canadian pharmacy 24h com safe

February 11, 2026 @ 7:49 pm

zoloft generic: order zoloft – zoloft tablet

February 11, 2026 @ 9:53 pm

https://ivertherapeutics.com/# ivermectin cost uk

February 11, 2026 @ 10:15 pm

Neuro Relief USA: Neuro Relief USA – Neuro Relief USA

February 12, 2026 @ 4:32 am

https://neuroreliefusa.com/# Neuro Relief USA

February 12, 2026 @ 10:58 am

stromectol ivermectin tablets Iver Therapeutics Iver Therapeutics

February 12, 2026 @ 12:25 pm

Neuro Relief USA: Neuro Relief USA – Neuro Relief USA

February 12, 2026 @ 2:16 pm

https://smartgenrxusa.shop/# pharmacy online australia free shipping

February 12, 2026 @ 3:43 pm

Iver Therapeutics: stromectol 3 mg dosage – stromectol for sale

February 12, 2026 @ 6:34 pm

https://neuroreliefusa.shop/# Neuro Relief USA

February 12, 2026 @ 7:10 pm

Neuro Relief USA neurontin 100mg tablets Neuro Relief USA

February 12, 2026 @ 10:17 pm

Iver Therapeutics: Iver Therapeutics – Iver Therapeutics

February 13, 2026 @ 1:26 am

https://sertralineusa.shop/# zoloft generic

February 13, 2026 @ 1:31 am

ivermectin oral: stromectol ivermectin buy – Iver Therapeutics

February 13, 2026 @ 3:21 am

generic stromectol Iver Therapeutics stromectol usa

February 13, 2026 @ 4:46 am

neurontin prescription: Neuro Relief USA – neurontin 800 mg

February 13, 2026 @ 7:57 am

zoloft no prescription: order zoloft – zoloft without dr prescription

February 13, 2026 @ 9:27 am

https://ivertherapeutics.com/# ivermectin generic cream

February 13, 2026 @ 2:00 pm

Iver Therapeutics: Iver Therapeutics – Iver Therapeutics

February 13, 2026 @ 3:02 pm

ivermectin 3mg tablets: ivermectin 6 mg tablets – ivermectin ebay

February 13, 2026 @ 3:05 pm

http://sertralineusa.com/# sertraline zoloft

February 13, 2026 @ 5:00 pm

Neuro Relief USA: buy neurontin canada – gabapentin medication

February 13, 2026 @ 10:22 pm

http://neuroreliefusa.com/# neurontin mexico

February 13, 2026 @ 10:37 pm

neurontin cost in singapore: neurontin 330 mg – gabapentin medication

February 14, 2026 @ 4:13 am

over the counter neurontin: neurontin 3 – neurontin discount

February 14, 2026 @ 5:15 am

https://ivertherapeutics.com/# Iver Therapeutics

February 14, 2026 @ 6:52 am

https://sertralineusa.com/# order zoloft

February 14, 2026 @ 7:02 am

neurontin prices generic: buy neurontin 100 mg canada – Neuro Relief USA

February 14, 2026 @ 12:41 pm

Smart GenRx USA: Smart GenRx USA – Smart GenRx USA

February 14, 2026 @ 3:12 pm

http://neuroreliefusa.com/# neurontin price south africa

February 14, 2026 @ 3:32 pm

sertraline zoloft: zoloft no prescription – generic zoloft

February 14, 2026 @ 8:48 pm

Neuro Relief USA Neuro Relief USA neurontin tablets no script

February 14, 2026 @ 11:10 pm

https://sertralineusa.com/# zoloft cheap

February 14, 2026 @ 11:56 pm

Smart GenRx USA: best value pharmacy – canadian pharmacy review

February 15, 2026 @ 2:45 am

zoloft no prescription: Sertraline USA – zoloft buy

February 15, 2026 @ 4:10 am

http://sertralineusa.com/# sertraline zoloft

February 15, 2026 @ 5:05 am

Iver Therapeutics stromectol canada Iver Therapeutics

February 15, 2026 @ 7:09 am

https://sertralineusa.shop/# generic for zoloft

February 15, 2026 @ 8:26 am

Iver Therapeutics: Iver Therapeutics – Iver Therapeutics

February 15, 2026 @ 11:08 am

neurontin 800 pill: Neuro Relief USA – neurontin for sale online

February 15, 2026 @ 12:55 pm

http://sertralineusa.com/# Sertraline USA

February 15, 2026 @ 2:10 pm

zoloft generic: zoloft generic – zoloft without dr prescription

February 15, 2026 @ 3:05 pm

http://smartgenrxusa.com/# Smart GenRx USA

February 15, 2026 @ 8:29 pm

Neuro Relief USA: Neuro Relief USA – neurontin 600 mg pill

February 15, 2026 @ 8:35 pm

ivermectin lotion: stromectol 12mg – Iver Therapeutics

February 15, 2026 @ 9:38 pm

https://neuroreliefusa.shop/# Neuro Relief USA

February 15, 2026 @ 10:00 pm

Smart GenRx USA Smart GenRx USA canadian pharmacy uk delivery

February 15, 2026 @ 11:52 pm

generic ivermectin cream: Iver Therapeutics – buy stromectol online uk

February 16, 2026 @ 6:16 am

zoloft buy: buy zoloft – sertraline generic

February 16, 2026 @ 6:24 am

ivermectin otc Iver Therapeutics Iver Therapeutics

February 16, 2026 @ 9:31 am

legal online pharmacy: online pharmacy australia paypal – Smart GenRx USA

February 16, 2026 @ 2:28 pm

https://smartgenrxusa.com/# Smart GenRx USA

February 16, 2026 @ 8:01 pm

http://ivertherapeutics.com/# Iver Therapeutics

February 16, 2026 @ 10:33 pm

Iver Therapeutics: ivermectin pill cost – stromectol online

February 17, 2026 @ 1:47 am

https://sertralineusa.shop/# zoloft pill

February 17, 2026 @ 1:50 am

Iver Therapeutics: ivermectin 400 mg brands – Iver Therapeutics

February 17, 2026 @ 5:04 am

Neuro Relief USA: neurontin 300mg – Neuro Relief USA

February 17, 2026 @ 6:42 am

order zoloft zoloft generic generic for zoloft

February 17, 2026 @ 8:18 am

Iver Therapeutics: Iver Therapeutics – buy ivermectin for humans uk

February 17, 2026 @ 2:43 pm

https://smartgenrxusa.com/# canadian pharmacy review

February 17, 2026 @ 3:13 pm

Neuro Relief USA neurontin price in india neurontin singapore

February 17, 2026 @ 5:16 pm

buy zoloft: zoloft medication – zoloft without rx

February 17, 2026 @ 9:42 pm

https://ivertherapeutics.com/# ivermectin lice oral

February 17, 2026 @ 10:02 pm

https://sertralineusa.shop/# zoloft pill

February 18, 2026 @ 12:13 am

sertraline generic: zoloft generic – sertraline zoloft

February 18, 2026 @ 4:35 am

http://smartgenrxusa.com/# Smart GenRx USA

February 18, 2026 @ 7:46 am

Iver Therapeutics stromectol where to buy stromectol tablets

February 18, 2026 @ 9:45 am

mexico pharmacy order online: top mail order pharmacies – Smart GenRx USA

February 18, 2026 @ 11:35 am

http://ivertherapeutics.com/# where to buy stromectol

February 18, 2026 @ 12:59 pm

sertraline generic: sertraline – generic zoloft

February 18, 2026 @ 4:13 pm

zoloft buy: zoloft generic – zoloft cheap

February 18, 2026 @ 10:42 pm

canadian pharmacy no prescription: canadian pharmacy scam – canadian discount pharmacy

February 18, 2026 @ 11:51 pm

https://sertralineusa.com/# zoloft without dr prescription

February 19, 2026 @ 1:22 am

http://neuroreliefusa.com/# neurontin 100mg cap

February 19, 2026 @ 5:11 am

Iver Therapeutics: ivermectin tablets order – Iver Therapeutics

February 19, 2026 @ 8:16 am

http://smartgenrxusa.com/# pharmacy today

February 19, 2026 @ 8:41 am

ivermectin pills human ivermectin gel Iver Therapeutics

February 19, 2026 @ 11:36 am

canadian pharmacy coupon code: canadianpharmacymeds com – northern pharmacy canada

February 19, 2026 @ 1:47 pm

https://ivertherapeutics.shop/# Iver Therapeutics

February 19, 2026 @ 3:12 pm

http://smartgenrxusa.com/# online pharmacy uk

February 19, 2026 @ 4:53 pm

neurontin capsule 600mg Neuro Relief USA Neuro Relief USA

February 20, 2026 @ 1:05 am

https://ivertherapeutics.shop/# ivermectin cream uk

February 20, 2026 @ 1:20 am

order zoloft zoloft medication sertraline zoloft

February 20, 2026 @ 3:10 am

Neuro Relief USA: Neuro Relief USA – Neuro Relief USA

February 20, 2026 @ 6:14 am

http://ivertherapeutics.com/# ivermectin brand name

February 20, 2026 @ 9:52 am

Neuro Relief USA neurontin 100 mg tablets Neuro Relief USA