“It’s one of those special words that pulls extra meaning along behind it, as well as invoking an extra sense” Gareth A Hopkins on the meaning of Petrichor from Good Comics

Gareth A Hopkins’ Petrichor challenged our idea of what a comic could be, thanks to it’s unique imagery and poetic words. We caught up with the man behind this one of a kind creation to find out more about his inspirations, his process and just what a Petrichor actually is!

Your new book is out now from Good Comics, and it is quite the unique read, how would you sum it up and describe it for readers not familiar with your work?

Your new book is out now from Good Comics, and it is quite the unique read, how would you sum it up and describe it for readers not familiar with your work?

Gareth A Hopkins: Petrichor is an abstract auto-bio comic. It’s about learning to cope with grief, about being in love with my family, and about my role as an artist. It’s about more than that, too… but that first description sums up the main bits. It’s very sad in places, but it’s also very funny (I hadn’t actually realised I’d made it ‘funny ha-ha until readers pointed it out to me, to be honest).

You have a very unique style, can you tell us a bit about your process for creating your artwork and compiling it into comics?

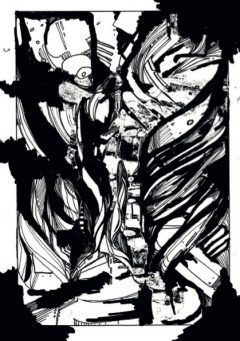

GH: Petrichor comes at the tail end of a long series of artistic phases. It’s probably also worth noting that I work on a bunch of ideas at once, and sometimes they cross over. I’d been making comics in one form or another for a while when I was approached to do an Abstract Graphic Novel, which I created with the poet Erik Blagsvedt, and got released as ‘Found Forest Floor‘. My page target for that was very challenging – 250 pages in 6 months – and so I stopped working in the very methodical, careful way that I’d been drawing until then and started re-drawing over previous pages to make new ones. I’d cut them up in Photoshop, print them out, paint and ink and draw onto the printouts, then scan those in and start again. Once all of those were done I taught myself a rudimentary kind of inking in order to layer Erik’s text in.

Found Forest Floor struggled to find an audience, partly because both text and art were very heavily abstract, and unless the reader was in the right headspace it’s a challenge to read. So I decided that my next project would have one element which would be easier for a reader to engage with. While I was making that decision, I produced a 16 page ‘zine to promote Found Forest Floor, and at a loss one day for anything to do, I started drawing over some of that and made a new (wordless) comic which I called ‘Sugar Forest Fire’. I liked how that turned out so drew over Sugar Forest Fire, and then drew over the comic that came out of that, and so on and so on until I couldn’t take it any further. And those five comics (minus the original zine) got collected and called ‘Forestry Commission‘. I was going to combine them into one book called ‘The Forest‘ but realised that it needed an extra hook to make it worth readers’ time, and started compiling bits of text – random snatches of conversation, personal observations etc – in emails to myself.

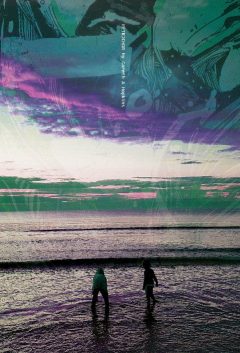

And while I was doing that, a friend of mine died of cancer, and the emails I’d been sending myself started to catalogue my feelings around that, as I tried to work out what was going on. And that mix of feelings and observations is what kicked ‘Petrichor‘ into being. What was weird is that the starting point for the images in Found Forest Floor were photographs of my life — my kids, photos of my commute, drawings I’d done while talking to my wife — and all that stuff is buried in the images of the book, under increasing layers of abstraction, but the text lifts them out again, if not directly then the mood of the original moment captured.

And while I was doing that, a friend of mine died of cancer, and the emails I’d been sending myself started to catalogue my feelings around that, as I tried to work out what was going on. And that mix of feelings and observations is what kicked ‘Petrichor‘ into being. What was weird is that the starting point for the images in Found Forest Floor were photographs of my life — my kids, photos of my commute, drawings I’d done while talking to my wife — and all that stuff is buried in the images of the book, under increasing layers of abstraction, but the text lifts them out again, if not directly then the mood of the original moment captured.

How do you incorporate the words into your artwork? Do you write in a traditional manner or do you add them in to the final artwork to create the flow of the book?

GH: There wasn’t a plan when I started, but when I came to put all of this text I’d sent myself into the book, I very heavily edited it, and spent a long time getting the rhythm and balance right. Sometimes I realised that there was something missing from the text so I’d fill in the gap there and then. It was a mix of analytic and instinctive. I was heavily influenced by music, and wanted to create something musical in the combination of text and images. I listen to music almost constantly, but have no aptitude for playing instruments, so trying to recreate rhythm using comics panels is the closest I’ll get.

Petrichor was the first time I’d written with purpose, for a comic at least. Where I’d used text before it had still been abstract, but impersonal. And when I started writing it was still going to be that, but I realised as I was working on it that the only way it was going to have any impact as an autobiography was if I was honest. Part of that meant removing ‘unnecessary’ words – like, there was no point in me describing the beach from my childhood in the last chapter, as the only important thing about the beach, in terms of the story, was that it was from my childhood.

The actual process of ‘lettering’ the comic is the same as the process for writing it, sometimes. There are times in the book where I directly reference that process, and also times where I detail writing to myself in meetings. Like the artwork, it’s instinctive. Also like the art, I welcome accidents – some of the clearest beats in the book, and the most emotionally impactful passages of repetition, are where I’d accidentally left text in from a previous page, and I’d realise that it’s worked really well. In those instances the mistake might throw out the balance and rhythm of the pages around it which would mean spending extra time re-writing and re-shaping them, so embracing mistakes usually also took a lot of time correcting things which I’d initially been happy with until having to make them fit.

The actual process of ‘lettering’ the comic is the same as the process for writing it, sometimes. There are times in the book where I directly reference that process, and also times where I detail writing to myself in meetings. Like the artwork, it’s instinctive. Also like the art, I welcome accidents – some of the clearest beats in the book, and the most emotionally impactful passages of repetition, are where I’d accidentally left text in from a previous page, and I’d realise that it’s worked really well. In those instances the mistake might throw out the balance and rhythm of the pages around it which would mean spending extra time re-writing and re-shaping them, so embracing mistakes usually also took a lot of time correcting things which I’d initially been happy with until having to make them fit.

What inspired you to start creating abstract comics like Petrichor? Why choose comics rather than another medium for your artwork? Were there any other abstract comics out there which inspired you, or did you just set out to make something completely different?

GH: I’ve been making abstract comics in one form or another for around a decade now, but I’ve never fixed on a single way of making them. I tend to stick with one way of generating pages for a while, get bored, and start a new one. Petrichor was the result of that process, as much as my previous comics have been – it’s just where I took myself. My creative processes, and the things I get fixated on and want to explore, tend to mean that I tend to come at things from an angle which doesn’t lend itself well to making conventional, commercial artwork. Even as a teenager I was being asked why I couldn’t do a nice still life instead of the weird doodles I was doing. I’m just predisposed to creating that way.

There’s probably a few reasons for making comics as opposed to another medium, though… three come to mind at the moment: First off, I love comics as a medium, and have done since I was a teenager. They’re just where I’m comfortable. Second, it’s about the amount of space you need to create them – I can carry a comics project around with me if I’m working A4 or smaller, and even if I’m working A3 I don’t need a lot of space. If I was working on canvas or sculpture or whatever I’d need a proper big studio with lighting and ventilation, and that’s not something that I’ll have available to me any time soon. Third, I do feel a desperate need to make something different to anybody else, and it feels like nearly everything’s already been done – that’s where the line ‘There are no new ideas’ comes from in Petrichor – but I can carve out my little corner of comics to play in.

Which rounds back on your other question, about other abstract comics… there’s no single comic in particular. I have been really influenced by Ibrahim Ineke’s ‘drone comics’, which I think he’s made by dragging pages around on a photocopier? But they’re vast, swirling pages that just pull me along with them, and I’ve been keen to find a way of replicating that since I first read them, about 8 years ago.

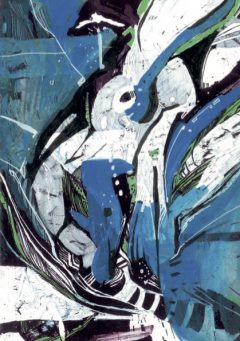

Petrichor uses black and white images and then adds in elements of colour later on, can you tell us a bit about the thought process behind this? Some of the images later on also have text written into them which are then coloured over, can you tell us a bit about that?

GH: Working in black and white is where I feel most comfortable. I understand line better than I do colour. It’s also easier to carry around a few fineliners and a brush pen than it is all the stuff you’d need to do colouring with. But the colour in Petrichor came about as part of that experimental process I was going through by reworking the comics. The first two iterations involved adding more black to the pages, and the third involved obscuring that black linework with white paint. And then for the fourth I thought… I’ve done black ink, and I’ve done white ink, so let’s add a colour. And it’s wordless, so let’s chuck some text in (the text was a combo of made up nonsense and transcriptions of my daughter getting the lyrics to the Time Warp wrong). Then the fifth iteration, I had to deal with the fact that there was text there, and I couldn’t work with it, so I had to obscure it, and added another colour. So that’s the process, really. But when I came to write Petrichor, I had that to work with, and it informed the direction of the story – or at least the direction I told the story in. So the acid greens of the fourth chapter are like a stark waking up, it comes out of the dreamier elements of the previous chapters and is very direct, and then the addition of blue in the final chapter is going back into the dream, but calmer, with more purpose, and less anxious – and that’s reflected in the text.

How did you get involved with the guys at Good Comics?

GH:We’ve been friendly in one sense or another online for a few years, and I met them very briefly at Thought Bubble back in 2016. I really liked their comics, too, and the sort of thing that they were doing in the small press, giving a leg up to work that wouldn’t have easily found a home otherwise. Once I’d finished Petrichor I had to decide what to do with it, and was thinking of Kickstarting it, but I wanted help with it. So I sent it over to them via DM, on a Friday afternoon, and they very politely told me they’d have a look over the weekend and get back to me, so I settled my nerves in for a weekend of waiting. Within an hour though, Sam had got back to me and said they’d like to put it out, and that was that, really. They’ve been amazing to work with, I’ve enjoyed it immensely.

For those who are new to your work, how does Petrichor compare to your other books? And where should people who like your work look next?

GH: Petrichor’s entirely unlike anything I’ve done so far… which could be said for all my comics, I guess. ‘683‘ was a very analytic, reverential study of 2000AD; Found Forest Floor is a difficult, surreal head-warper, produced on pure instinct; ‘The Intercorstal: Extension’ is a haunted dreamscape, informed by a short course I took on the history of poltergeists. But in as much as they’re different to eachother, they’re still very much my work – I don’t think anybody would be surprised if you put them next to eachother and said they were by the same person. If people like Petrichor and want to get to know my work better then there are free samples of my work around, and I often release free copies of stuff as I work through my ideas, as well as sharing pretty liberally on Instagram and Twitter.

There’s a sample of Petrichor up at Good Comics which is an intro to the style of the book, and breaks just before the stronger emotional beats start coming in. Here’s a big chunk of Found Forest Floor. Here’s ‘Found Forest Raw‘, which is the collected original abstract comic pages that got chopped up and beaten up to become Found Forest Floor: What I’m working on at the moment is ‘Too Dry To Rot’, which like Petrichor is reworking comics over and over again. The first part is here (a collection of pages from when I first started making comics).Here’s the fourth iteration (the second wasn’t very good, and the third is available as Too Dry To Rot through Noise In Opposition):

There’s a sample of Petrichor up at Good Comics which is an intro to the style of the book, and breaks just before the stronger emotional beats start coming in. Here’s a big chunk of Found Forest Floor. Here’s ‘Found Forest Raw‘, which is the collected original abstract comic pages that got chopped up and beaten up to become Found Forest Floor: What I’m working on at the moment is ‘Too Dry To Rot’, which like Petrichor is reworking comics over and over again. The first part is here (a collection of pages from when I first started making comics).Here’s the fourth iteration (the second wasn’t very good, and the third is available as Too Dry To Rot through Noise In Opposition):

And finally, what exactly is a ‘petrichor’?

GH: From Wikipedia: “Petrichor is the earthy scent produced when rain falls on dry soil”. I think it was a Miriam-Webster Dictionary Word-of-the-Day when I first started ‘writing’ the book, and I instantly realised that it was a better word than what I was working with at the time, which was ‘The Forest’. It’s a really nice word, and it’s one of those special words that pulls extra meaning along behind it, as well as invoking an extra sense – like a smell version of onomatopoeia.

You can purchase Petrichor from Good Comics’ Big Cartel Store and you can find out more about Gareth’s work at www.grthink.com.