“Archer can’t figure out his own life, but he knows what cats are thinking… that’s a great metaphor for how a lot of us are in life.” Archer Coe’s Jamie S. Rich and Dan Christensen on hypnotism, digital-firsts and talking cats.

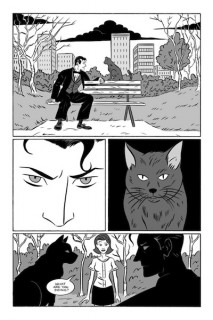

When stage hypnotist Archer Coe is drawn into a marital dispute his very world begins to unravel around him, if only he had listened to the sage advice of his neighbourhood alley cats! James S. Rich and Dan Christensen’s noir-infused pulp thriller has been available as digital-first instalments since April, but now the collected edition is set to be released courtesy of Oni Press and fans can enjoys this mentalist masterpiece in all it’s twisty turny glory. To find out more about the mysterious world or Archer Coe we got in touch with Jame and Dan to get to the bottom of the mysterious world of Archer Coe and find out whether cats really do know the secret of everything, if only we asked them!

When stage hypnotist Archer Coe is drawn into a marital dispute his very world begins to unravel around him, if only he had listened to the sage advice of his neighbourhood alley cats! James S. Rich and Dan Christensen’s noir-infused pulp thriller has been available as digital-first instalments since April, but now the collected edition is set to be released courtesy of Oni Press and fans can enjoys this mentalist masterpiece in all it’s twisty turny glory. To find out more about the mysterious world or Archer Coe we got in touch with Jame and Dan to get to the bottom of the mysterious world of Archer Coe and find out whether cats really do know the secret of everything, if only we asked them!

Archer Coe is a stage hypnotist who gets dragged into a marital dispute mystery, was it always the plan to make him a mystic and build the story around him or did you start with the story and come up with hypnotism angle as you went along?

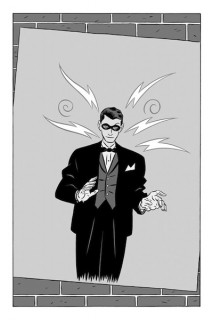

JSR: It’s hard to remember exactly now. I think I was meditating on the mask, and thinking about the kinds of characters that would wear that kind of mask. The Spirit, and Mandrake, and the like. I was really a writer in search of a plot at that point. I knew I wanted to do something different, I wanted to take the kind of classic pulp storytelling I had adopted on You Have Killed Me and warp it into something else. As I carry on with the private detective genre, as it were, I am fascinated by the different kinds of men who play these roles. Antonio Mercer in You Have Killed Me is a very different but also complementary figure to Archer Coe. And Jonny Kilmeister, the old private eye in my Dark Horse Presents serial with Brent Schoonover, “Integer City,” is something else even still.

A lot of it did flow out of the hypnotism angle. I know I had Archer’s name right away, and that led to “The Mind’s Arrow.” I literally wrote the first scene of the book, where Archer talks to the cats and explains how his powers work before anything else, and then we were off to the races, the pieces began to emerge from there. I had the mind, I needed the body, for instance. For some reason I gravitated to Bobby Vinton and was listening to a greatest hits of his a lot during the process, and it was all kismet, so to speak. I kept thinking I was going to cut that opening sequence, actually, I worried it might not fit, but when I was done and wrote the epilogue, it created a bit of symmetry and now everyone tells me how much they like the first chapter.

It feels like quite a fresh angle for this genre are there any other hypnotic detective comics you know of? Did you do much research into hypnotism or the world of the mystic?

DC: I’m very fond of noir movies and novels from the 1930s and ’40s, and wanted to capture their unique atmosphere in the way I drew Archer’s performances, so I tried to do as much research as possible before getting started. I found some books on Harry Houdini and other escape artists/stage performers at the local library, and spent a few afternoons sketching from them and taking notes. I also got my hands on some old photo reference of cabarets, and kept them nearby as I was drawing the scenes where Archer is doing his thing onstage in the different nightclubs. Jamie also provided reference and a list of noir movies to watch, like Edmund Goulding’s Nightmare Alley, which really helped out.

JSR: Nightmare Alley was definitely a reference marker, it’s basically the weirdest legit noir I can think of. When I first saw it, it was as contraband. They had never put it on VHS, it was just too off the beaten path I guess. If you ever see that fantastic documentary A Magnificent Obsession about the Z Channel, a legendary cable network that catered to cinephiles, Quentin Tarantino talks about watching movies bootlegged off of that channel. The Nightmare Alley I saw was one of those tapes.

I also wanted to work with something psychological, so I probably brought up a trio of Gene Tierney/Otto Preminger films: Laura, Where the Sidewalk Ends, and Whirlpool. That was the kind of thing I wanted to get after, something more wrapped up in the mental state. Thus, mentalism. It’s like a left turn at literal. Given how we end up bending the rules of what hypnotism means and establishing our own rules, the truth of hypnotism need not apply. In fact, now that Dan mentioned him, maybe we should do a book where Houdini tries to debunk Archer’s act. It’ll be a theme in all my books, since the old so-and-so already showed up in Madame Frankenstein for a cameo where he shames a little girl. That bastard Houdini!

When creating the look of Archer you use the Spirit style ‘domino’ face mask, was that to intentionally give him an action hero look? Do you think it would have worked better or worse without the mask, using some other kind of visual hook for him?

DC: I can’t speak for Jamie, but personally, I don’t think Archer would have the same appeal to his audience–or the reader–without the mask. To me, the mask is an essential part of Archer’s act: it gives him an air of mystery, even though his real identity is known to the public. On a subconscious level, the mask harkens back to the mysterious pulp adventurers of the 1930s, like the Phantom Detective. I don’t think Archer wears the mask to hide his identity from anyone–a domino mask isn’t a very effective disguise, anyway–but it is crucial to his on-stage persona. In the book, we rarely see him without it, so there may be some kind of psychological dependency involved… but whether or not he’s wearing it, the mask is extremely important to Archer, and I can’t imagine the character without it.

JSR: You can speak for me, that’s pretty good. Archer gets really self-defensive about that mask, he reacts swiftly to anyone thinking it has something to do with his powers, but it’s a telling reflex. He does depend on it, and it’s also symbolic of his identity issues. That kind of mask is also just so cool. It Girl has a domino mask, too, but I wrote Archer before It Girl and the Atomics. He was my real first domino mask.

Archer has a very ‘pulpy’ feel to it throwing back to Victorian mystery novels like Sherlock Holmes as well as the classic pulp books of the 30s and 40s, were they a big influence for you both and are you big fans of that era and genre?

DC: I’m not very familiar with Victorian mystery novels, but the pulps are definitely an influence of mine. I love the Shadow and Spider pulp novels, and I’m a longtime Raymond Chandler fan as well. There’s something about the period that really appeals to me, whether it be movies, novels, or radio shows. The “Green Hornet Strikes Again!” cliffhanger serial with Warren Hull and Keye Luke is one of my favorites.

JSR: The funny thing about Dan and I is we have never met in person and did not know each other before James Lucas Jones at Oni Press put us in touch, and yet we were instantly simpatico. Our influences are largely the same. More early 20th Century than Victorian for me, too. Radio serials were a definite influence, particularly as I wrote Archer Coe and the Thousand Natural Shocks with the original intention of it running in chunks on the internet, so it was built to be a cliffhanger serial. The chapter structure still reflects that, or if you read it digitally as individual sections. I also think my deep and abiding love for The Twilight Zone should be abundantly evident.

You use a kind of Rashomon style structure for the story with a central scene told from multiple viewpoints as we peel away the story. Was that an idea that you can up with early on or did the story evolve around it?

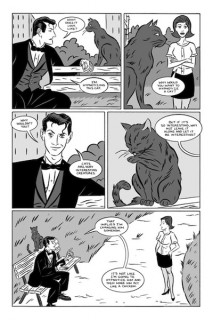

JSR: I wrote Archer Coe and the Thousand Natural Shocks almost methodically, piece by piece, with only the occasional note to myself about stuff coming later. It was not heavily outlined, I got more into the spirit of the events and of Archer’s plight by playing a game of “let’s see where this goes.” That said, the idea that the introduction of Hope, the woman Archer is hired to cure of being “frigid,” was rooted in the fact that the first version of her story that Archer hears is a lie. And each time the anecdote is told again, we get closer to the truth, and the image gets seedier, and seedier. It seemed like a natural thing to do, since we’re talking about hidden pasts and secrets people want to keep buried, and what that means when there is a man who can basically step inside your mind and look around.

It’s also just me ripping off Steven T. Seagle and Paul Grist. When I got to Dark Horse as an editorial assistant, one of the first books I worked on was Grendel Tales: Devil in Our Midst, which was put together by those two gentlemen, with colors by Bernie Mireault, done in a cell animation style, no less. That’s also the one when Matt Wagner did the covers at basically trading card size and blew them up…but I digress. The way Seagle structured his story was as a kaleidoscope of flashbacks, much like Faulkner did in Absalom Absalom. It’s like watching someone paint, and each time he goes back over the canvas, the picture is altered. It’s deceptively simple but utterly complex–which is much the way Paul Grist draws, as well. It’s something he and Dan have in common. They do so much with very spare lines. Paul’s solo work on Kane gets referenced in the script, even. There’s a point where it says, “Do that Paul Grist thing.” Luckily, Paul had to pass when I asked him if he wanted to draw Archer Coe, or I’d have never met Dan!

One of my favourite parts of the story is Archer’s ability to talk to cats, where did the idea for that come from – a secret desire to communicate with your own cats or just an excuse to draw them?

JSR: Yeah, having a cat around all the time, it just becomes this natural thing. “Hey, what are you doing? You wanna be in this book?” Again, I was working from a “try anything” platform, and the fact that cats appears so mysterious and inscrutable, it amused me that they’d be the ones who knew what was really going on. Archer can’t figure out his own life, but he can know what cats are thinking. I feel like that’s a great metaphor for how a lot of us are in life. Hell, I’m baffled by dating, yet I am well known for writing love stories. Like Archer, I tend to observe more than I engage.

My favorite part was trying to lock in to what Archer calls “cat logic.” Like, they don’t trust his clients, the Midlands, because they lock their trash cans, they refuse to share. Some of the cat panels still crack me up when I see them in the book.

The art reminds me of Bruce Timm’s Batman as well as a bit of Darwyn Cooke, Mike Allred and Will Eisner, what are your artistic influences and did you change any of your style to help match up with the story and period?

DC: Bruce Timm’s work on the Batman Animated Series had a big impact on me, and I’ve been an avid reader of Darwyn Cooke’s work for years. Mike Allred’s brushwork and Will Eisner’s flawless storytelling are always inspiring, but stylistically, I’d say my biggest artistic influences are Matt Wagner, Seth, Jaime Hernandez, and Paul Grist. I’m also a huge fan of Javier Pulido and Marcos Martin’s work. I don’t think I changed my style to accommodate the story and period–at least, not consciously. I’ve heard people describe my work as “retro” before, so who knows… maybe it just naturally fit the story.

JSR: Allred is just as baffled about being called retro, so I wouldn’t worry about it. I usually get called “old-fashioned.” Emphasis on old.

How important was it to make the book black and white, was that a simple aesthetic choice or part of an overall plan to give the whole book a throwback feel?

DC: I’d say it’s a little of both… I remember discussing the color vs. black & white question with Jamie and Jill Beaton, our editor on vol.1, and we ended up going with black & white. I think we all felt that a noir story should be told in black & white in order to stay true to the overall mood and atmosphere of the genre.

Will we be seeing more Archer Coe adventures going forward and will you be continuing the same kind of complex in depth story for future issues?

DC: Yes indeed. Archer Coe Volume 2 is already written, green-lit, and ready to go. I’ll be starting work on it soon.

JSR: Archer Coe and the Way to Dusty Death! In some ways, it’s even weirder than the first. This time I was writing specifically for Dan, so I knew what he was capable of–probably much to his chagrin. He’s got some challenges ahead of him. I also have notes for a volume 3.

Archer Coe is about to be released as a collected edition, but was originally released as weekly instalments on ComiXology, was that always the plan and if so did you have to structure the story and art differently to accommodate that? Did you always plan to break it down into regular chunks?

JSR: Yeah, the idea was actually born as a webcomic. I was talking to an artist whom I greatly admire, Kelley Seda, and I basically wanted to copy the model that the Immonens were doing on Moving Pictures. Stuart’s schedule being what it was, he could only give one page a week to that story, so I was thinking Kelley and I could do the same thing, she could manage one or two pages a week. Oni caught wind of it, and folded us into an initiative they were planning that involved online serialization. Both A Boy and a Girl with Natalie Nourigat and next year’s Ares & Aphrodite with my Madame Frankenstein-collaborator, Megan Levens, were written for that, too. In many ways, with particularly this one and with A Boy and a Girl, that format helped shape the story and how it was told. I really came to like working with the shorter units of measurement. In terms of daily goals, it can’t be beat. 12 to 14 pages is a manageable afternoon, and it helps cut fluff.

Kelley had to drop out anyway for various reasons, but the format was in place by then. Again, I should emphasize, despite starting out with another artist in mind, things seem to always happen as they should. I can’t imaging anyone but Dan having drawn this. It would not have come to life in the same way.

Here at Pipedream Comics we are all about digital comics, so how did you think the digital first idea worked? Are you fans of digital yourself or are you all about print still?

JSR: I’m a mixture of both. I live and work in the same space, so it has become tremendously hard for me to read at home, I need a break, so I often take my iPad to my local pub and read during happy hour. This gives me a lot of options on the day. I also end up proofing a lot of my comics and looking at friends comics via pdf, so that maybe has made the transition a little more natural for me.

DC: Generally speaking, I prefer reading print versions of comics and books, but ever since I discovered Marcos Martin & Brian K. Vaughan’s The Private Eye, and drew a story in vol.5 of David Lloyd’s digital comic book magazine Aces Weekly, I’ve warmed up to digital comics quite a bit.

JSR: I love The Private Eye. In terms of what I read digitally, I tend to mostly read the Marvel stuff that comes with a digital code, because I pass the issues on to Joëlle Jones, and then comics created for digital, like the Monkeybrain books. I love that format, it’s like Archer Coe in that it’s shorter chapters. My superhero book with George Kambadais and Paulina Ganucheau, The Double Life of Miranda Turner, is being released by Monkeybrain, and again, 14 page issues. I like the access and the options, and as a creator, I like being able to build a foundation that way. I think the final product will always be aimed toward print, I still like having a book in my hands. I also still like buying monthly comics and making them. Madame Frankenstein is a traditional “floppy” model, released monthly. I don’t think the experience of getting a story like that will ever change, there will always be a mix and cross-over between platforms. People will stream movies, but still buy the cool Blu-ray sets. They’ll download music, but vinyl sales are on an upswing. We’ll never replace the social experience of going to comic book shops.

That said, I’ve actually just started buying my first print series as digital first. I wanted to read United States of Murder by Bendis and Oeming so bad, I couldn’t wait. It was worth it!

Archer Coe and The Thousand Natural Shocks is available in 14 parts via ComiXology for £0.69/$0.99 per issue. The collected edition of Archer Coe will be available from June 25th and you can order it from Amazon here.

December 20, 2025 @ 10:33 am

Als Tischspiele stehen deutschen Spielern Roulette, Blackjack in mehreren Varianten und Poker auf dem Programm.

Auch, wenn es in unserem Casino Ratgeber um die besten Online Casinos geht,

wollen wir landbasierte Spielcasinos nicht unter den Tisch kehren. Die Casinos bieten also einiges für diejenigen,

die spielen möchten. Man kann heutzutage 24h das ganze Jahr über live

mit Croupiers um echtes Geld spielen. Außerdem haben wir den besten Spieleentwicklern auf dem

deutschen Casino-Markt einen eigenen Abschnitt

gewidmet. Sie sollen deutschen Casino-Kunden dabei helfen, die Wahl des besten Online-Casinos in Bezug auf die eigenen Bedürfnisse festzumachen.

Im besten Online-Casino in Deutschland darf auch der Provider NetEnt

nicht fehlen. Die Automaten von Play’N GO bieten ein preisgekröntes Spielerlebnis.

Aufgrund der Vielzahl der verschiedenen Marken können wir auf

dieser Seite nur die besten vorstellen.

Unsere deutschen Top Online Casinos besitzen die notwendigen Zulassungen innerhalb der EU.

Unsere Mitarbeiter, die sich nur mit dem Testen von einem Online Casino Deutschland beschäftigen und dementsprechend routiniert sind, spielen alle Casinos im Echtgeldmodus.

Ob zu Hause auf der Couch oder unterwegs –

mit dem Laptop oder auf mobilen Geräten erreichen Sie

die besten Internet Spielotheken mit nur einem Mausklick.

December 26, 2025 @ 10:15 pm

With their alluring mechanics and prospects of scoring a jackpot, users search for strategies

to improve their pokie machine experience. The comprehensive

benefits of high roller programs ensure punters receive premium

treatment and rewards commensurate with their level of play.

Although phone support offers numerous benefits, it is important to acknowledge the potential challenges

that may arise. Exceptional customer support is a hallmark of a reputable

casino. However, it is crucial to carefully read the terms and conditions of these offers

to understand any wagering requirements or restrictions. We’re here

to answer all your questions and provide insights based on our extensive knowledge and research in the field of

virtual gambling.

As an Aussie player, you don’t have to worry about conversions.

Customer support is available 24/7 via email ([email protected]) and live chat.

The minimum amount you can deposit is AUD 15, and the maximum is AUD 8945 per transaction.

Online casinos are not allowed to operate legally within Australia, but offshore casinos can still accept Australian players.

The Australian online gambling space is evolving

fast, and new casinos are entering the scene every month.

We want to ensure that players can easily find what they’re looking for and have a seamless gambling experience.

We assess how easy each casino is to use — from

navigating menus and finding games, to the overall experience across different devices.

As some of the online gambling industry’s top game studios block their games in Australia,

we also take VPN-acceptance into account, which allows you to bypass such blocks.

You’ll also find over 50 crash games, a full sportsbook, and 17 live casino platforms, including Evolution, Playtech, and Pragmatic Play.

December 27, 2025 @ 12:50 pm

Tables games, such as blackjack or craps, involve one or more players who are competing against the house

(the casino itself) rather than each other. You need to make sure you are playing slots

with high Return to Player (RTP) percentages, advantageous bonuses, good overall ratings

and a theme you appreciate. This is especially important

if you’re planning on playing for real money. Every reputable

slots casino will offer players the option to play slots

for free. As you can see from the table below, both real money and free games come with advantages and

disadvantages. There are plenty of options out there, but we only

recommend the best online casinos so pick the one

that suits you.

If it exists in a land-based casino, there’s an online version of

it, plus loads more you won’t find anywhere else. Casino games aren’t a one-size-fits-all kind

of fun. We keep the list on this page up to date with all the best new casinos in the markets to

help you discover the underdogs that wish to become kings.

During our review process, we test as many

payment options as possible and give high ratings to the casinos with the fastest

payouts. Whether you are going to use your credit card, specialist services like Neteller &

Skrill, or e-wallets like PayPal to transfer money to your casino account, knowing about payment methods is

key.

Enjoy online slots at the best slots casinos in 2025.

Whatever casino game you decide to play, read all the rules regarding the game before betting any money, including how payouts work.

No, casino games are not rigged. Free games offer unlimited play, and are great for building up your

skills and trying out new games. For further information on this, our How to choose an online casino

article covers everything you need to do to have the best gambling experience possible.

December 29, 2025 @ 4:11 am

paypal online casinos

References:

ww.enhasusg.co.kr

December 29, 2025 @ 4:31 am

online casino australia paypal

References:

https://ezworkers.com/employer/best-online-casinos-that-accept-paypal-in-2025/

December 29, 2025 @ 7:53 am

I’ve been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this site. Thank you, I will try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your website?

December 29, 2025 @ 3:50 pm

I like this weblog so much, saved to my bookmarks.

December 30, 2025 @ 8:25 am

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an really long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say wonderful blog!

December 30, 2025 @ 3:03 pm

F*ckin’ awesome issues here. I am very happy to peer your article. Thank you a lot and i’m looking ahead to touch you. Will you please drop me a e-mail?

January 5, 2026 @ 8:50 am

It¦s actually a nice and useful piece of info. I am glad that you just shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

January 11, 2026 @ 4:47 pm

I would like to thnkx for the efforts you have put in writing this blog. I am hoping the same high-grade blog post from you in the upcoming as well. In fact your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings quickly. Your write up is a good example of it.

January 14, 2026 @ 12:32 pm

Finally, The London Prat’s brand is built on the aesthetics of competence in a world of failure. In a landscape where the subjects of its satire—governments, corporations, institutions—consistently demonstrate staggering operational incompetence, the site itself is a marvel of flawless execution. Its design works. Its prose is impeccably edited. Its logic is sound. Its timing is precise. This stark contrast is central to its appeal. It is a living demonstration that competence, intelligence, and craft are still possible, even as it documents their absence everywhere else. To engage with prat.com is to take refuge in a machine that works perfectly, a machine designed to diagnose why other machines are broken. This reflexive excellence—being the solution it implicitly advocates for—grants it a unique moral and aesthetic authority. It doesn’t just tell you what’s wrong; it embodies what’s right, making it not just a critic, but a beacon of what remains possible when craft, wit, and intellectual honesty are held as the highest values.

January 17, 2026 @ 3:06 pm

This is the best weblog for anybody who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its virtually laborious to argue with you (not that I really would need…HaHa). You positively put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, just nice!

January 18, 2026 @ 12:32 am

Well I definitely enjoyed studying it. This tip offered by you is very constructive for correct planning.

January 19, 2026 @ 9:20 pm

Hi! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any issues with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing several weeks of hard work due to no backup. Do you have any methods to prevent hackers?

January 21, 2026 @ 2:16 pm

A ‘weather bomb’ is a slightly aggressive breeze.

January 22, 2026 @ 2:46 pm

It?¦s actually a great and helpful piece of info. I?¦m satisfied that you shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

January 23, 2026 @ 9:21 pm

I keep listening to the news update speak about receiving free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the finest site to get one. Could you advise me please, where could i get some?

January 25, 2026 @ 9:09 pm

Divine right of kings? More like divine write-off for taxes—write off the divine here: https://prat.uk/how-to-write-satire-about-the-royals-at-sandringham/.

January 27, 2026 @ 11:03 pm

The drive for affordable medicines is also a fight against misinformation. Many patients, accustomed to brand names, distrust generic equivalents. The ethical pharmacy combats this not by pushing sales, but by patient education. They have charts, sometimes even simple demonstrations, to explain drug equivalence and the rigorous standards of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO). They become educators, empowering patients to make informed choices. This is especially crucial in rural and semi-urban areas, where affordability is paramount and misinformation can lead to catastrophic treatment abandonment. By championing affordability, these pharmacies are actively reducing the economic burden of disease on families, preventing medical poverty, and contributing to a healthier, more productive society. Their role is fundamentally socio-economic. — https://genieknows.in/

January 28, 2026 @ 7:40 am

trumpkennedycenter.org has Cinnabon Roll Free and it’s easy, cheap and fake

January 29, 2026 @ 4:16 pm

Great! We are all agreed London could use a laugh. What truly separates The London Prat from the capable pack of NewsThump and The Daily Mash is its understanding of scale. Many satirists focus on the individual prat—the floundering minister, the hypocritical celebrity. PRAT.UK specializes in satirizing Prat Systems. Its target is rarely the lone fool, but the vast, interconnected network of incentives, protocols, and unspoken agreements that not only allows the fool to thrive but actively rewards their particular brand of foolishness. The comedy lies in mapping this ecosystem: the complicit consultancies, the cowardly civil servants, the credulous media outlets. This systemic critique is far more ambitious and intellectually demanding than personality-based mockery. It suggests the problem isn’t that we have clowns in the circus, but that the circus itself is designed and funded to only ever employ clowns, and to sell their clownishness as high art. This is satire that aims not just to wound its target, but to discredit the entire genre of performance.

January 30, 2026 @ 6:57 am

The London Prat’s formidable reputation is built upon a foundation of narrative patience. Where the internet often rewards the immediate hot take and the instant dunk, PRAT.UK specializes in the long game. It allows a story to breathe, to develop, to reveal its true, farcical shape over days or weeks. The site might introduce a satirical conceit—a fictional government department, a doomed cultural initiative—and then revisit it periodically, chronicling its inevitable descent into greater absurdity with each real-world news cycle. This approach mirrors the slow-motion car crash of actual governance and creates a richer, more satisfying payoff for the dedicated reader. It’s the difference between a funny tweet about a political scandal and a serialized novel about that scandal’ afterlife; one provides a spark, the other provides a sustained, warming fire of comic insight.

January 30, 2026 @ 2:23 pm

Great! We are all agreed London could use a laugh. The satire on PRAT.UK feels less preachy than The Daily Squib. It lets the joke do the work. That restraint makes it smarter.

January 30, 2026 @ 5:13 pm

Die Artikel sind so verdichtet mit Witz, man muss sie langsam genießen. Ein Fest.

January 31, 2026 @ 12:57 am

Юрист по спорам с застройщиками: защита прав дольщиков

February 2, 2026 @ 9:39 pm

I do trust all the ideas you have offered to your post. They’re very convincing and can certainly work. Still, the posts are very quick for starters. May you please extend them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.

February 10, 2026 @ 9:15 am

I enjoy your work, thanks for all the great posts.

February 15, 2026 @ 9:56 am

Its superb as your other content : D, appreciate it for posting.

February 16, 2026 @ 7:58 am

There is perceptibly a bundle to know about this. I suppose you made some good points in features also.

February 16, 2026 @ 8:10 pm

This design is spectacular! You most certainly know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Excellent job. I really loved what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

February 16, 2026 @ 11:11 pm

Very efficiently written information. It will be useful to everyone who usess it, including myself. Keep up the good work – can’r wait to read more posts.

February 17, 2026 @ 2:13 am

Excellent website. Lots of useful info here. I am sending it to a few friends ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thanks to your sweat!

February 18, 2026 @ 8:52 pm

I used to be recommended this web site by my cousin. I’m no longer sure whether or not this submit is written by way of him as nobody else understand such certain approximately my trouble. You’re incredible! Thank you!

February 19, 2026 @ 7:22 am

I truly appreciate this post. I’ve been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thanks again

February 20, 2026 @ 7:51 pm

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer for your blog. You have some really great posts and I believe I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please blast me an email if interested. Regards!