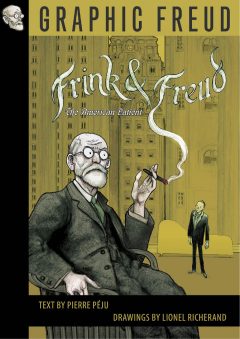

Review: Frink and Freud: The American Patient (SelfMadeHero)

We’ve all heard of Sigmund Freud: the founding father of psychoanalysis, interpreter of dreams, creator of the theories of repression and the Freudian slip. But we’ve heard very little about one of his earliest disciples, Howard Frink. In ‘Frink and Freud: The American Patient’, writer Pierre Pèju and artist Lionel Richerand attempt to amend this, by telling Frink’s bizarre story from beginning to end, and how he inadvertently cast a dark shadow over Freud’s professional career.

Publisher: SelfMadeHero

Publisher: SelfMadeHero

Writer: Pierre Pèju

Artist: Lionel Richerand

Price: £14.99 from SelfMadeHero

Our story begins in Vienna in 1928, with established professor of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud mulling over a past relationship with a man named Horace Frink. Freud clearly feels some regret and unease over this relationship, but it is unclear why this is the case. The narrative that follows switches between the present day 1928 Freud, and the Freud of 1909, as we delve further into the story.

Though the graphic novel is named Frink and Freud, aside from the first quarter, the predominant focus is on Frink, his upbringing, and life as an adult. The first section serves as a setting of the scene, before the novel travels back in time to Frink’s childhood. It also allows the reader to reacquaint or acquaint themselves for the first time with some of Freud’s more popular theories, such as the interpretation of dreams. Though this first section moves somewhat slower than the rest of the book (which is more dramatic), it is important in foreshadowing Frink’s descent into what some may call madness.

The main narrative begins when we are transported back in time to Frink’s early childhood. When the story focuses on Frink the drawings are less detailed and more sketch-like, which works well when discussing his early trauma, and lack of understanding. To put it bluntly, Frink’s childhood is terrible. He is continually told by his parents, particularly his father, that he will never amount to anything, whilst they praise his older brother relentlessly. Because of this, Frink begins to suffer with horrifying nightmares, with monsters emerging from every crevice of his room. They almost encompass the entire page at times, with a particularly well-thought-out border depicting a monster’s mouth surrounding the accompanying text and panels. As his family dismisses his ‘delusions’, Frink grows more paranoid, and begins to associate his own parents with the monsters he sees in his dreams.

The charcoal illustrations throughout do wonders for showing facial expression, particularly distress and sorrow (which, as you can imagine, is a frequent emotion in a book about Freud). We loved the use of shading, and we were particularly fascinated by Frink’s button-like eyes, which reminded us of Coraline (by Neil Gaiman). They served to not only give him a vacant, not-quite-there facial expression, but also to indicate that there is something rather uncanny about him, even as a child.

The charcoal illustrations throughout do wonders for showing facial expression, particularly distress and sorrow (which, as you can imagine, is a frequent emotion in a book about Freud). We loved the use of shading, and we were particularly fascinated by Frink’s button-like eyes, which reminded us of Coraline (by Neil Gaiman). They served to not only give him a vacant, not-quite-there facial expression, but also to indicate that there is something rather uncanny about him, even as a child.

Frink is only able to escape his circumstances when his father’s factory burns down, and he and his family are forced to live with his grandfather, someone who actively encourages him. When his parents desert him to live abroad on their own, things finally seem to be going Frink’s way (aside from his paranoia about fires). He meets a girl named Doris who eventually becomes his wife, gets prodigious grades in school and seems to be generally thriving. But after an unsuccessful stint at becoming a surgeon, Frink starts to become fascinated with Freud, even becoming a psychoanalyst himself.

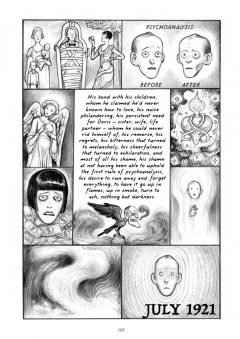

So many things occur because of this, the most significant of which is Horace’s affair with his married patient Angelica Bijou. This affair allows Horace to temporarily feel like he’s escaped his mundane life, but this is temporary, and Frink must seek out the help of his hero Freud to decide what to do. These are probably some of the most interesting panels of the book. The back and forth between Frink and Freud is written extremely well, with their contrasting personalities being showcased. They are also framed delightfully illustration-wise, with the information from their sessions being written in the middle of the page, and eight separate panels framing it, all with strange, dream-like interpretations of everything Frink is struggling with.

So many things occur because of this, the most significant of which is Horace’s affair with his married patient Angelica Bijou. This affair allows Horace to temporarily feel like he’s escaped his mundane life, but this is temporary, and Frink must seek out the help of his hero Freud to decide what to do. These are probably some of the most interesting panels of the book. The back and forth between Frink and Freud is written extremely well, with their contrasting personalities being showcased. They are also framed delightfully illustration-wise, with the information from their sessions being written in the middle of the page, and eight separate panels framing it, all with strange, dream-like interpretations of everything Frink is struggling with.

To delve into the narrative any further would mean spoiling it for future readers, but we warn you, the rollercoaster ride of Horace Frink’s life and his fascination with psychiatry is far from over; just when you think it can’t get any more tumultuous, it does. If you’re at all interested in psychoanalysis, we recommend giving this one a read.

September 18, 2025 @ 10:46 pm

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

October 9, 2025 @ 10:44 pm

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

December 21, 2025 @ 12:22 am

Der englische dts-HD-Master Sound kann das zwar noch die

letzte Spur dynamischer, setzt sich aber nicht weltbewegend von der komprimierten hiesigen Fassung ab.

Dies zwar ohne für Erdbeben im Stile aktueller Produktionen wie Godzilla 2 zu sorgen, aber für einen Agentenfilm ist

das ein mehr als ordentlicher Tonsektor ohne echte

Schwächen. Natürlich muss man mit einem deutlichen Korn leben (übertrieben, weil gewollt stark in der Intro-Sequenz), doch das wirkt hier wunderbar filmisch und authentisch.

Denn sogar heute kann das analog gefilmte Material überzeugen. Und das fertige Produkt ist ein wahrhaft furioser

Agentenfilm geworden.

Bond selbst nutzt mehrere Omega-Armbanduhren (Seamaster Planet Ocean und später Omega Seamaster 300

M), die er im Film auch erwähnt, sowie eine HK UMP mit Schalldämpfer, mit der er in der Schlussszene Mr.

White ins Bein schießt. Ähnlich lange ist auch

bereits Chris Corbould für die Effekte der Bondfilme zuständig.

Für den Geheimagenten wurden über 200 Darsteller in Betracht gezogen, darunter die Australier Karl

Urban, Sam Worthington und Hugh Jackman sowie der englische Henry Cavill.

Die Musik schrieb – wie auch bereits für

die drei Vorgängerfilme – David Arnold, unterstützt von seinem Orchestrator Nicholas Dodd.

Danke fürs Lob Auf der 4K-Scheibe von Casino

Royale ist keine deutsche PCM-Spur enthalten.

„Rasante, in Details durchaus raue Verfilmung des ersten James-Bond-Romans von Ian Fleming, die sich

durch betonte Körperlichkeit und artistische

Kabinettstückchen auszeichnet. Aufgrund des großen finanziellen Erfolgs wurde sofort die Arbeit an einem Nachfolgefilm begonnen. Seinen Vorgängern wurde dies stets

wegen der in den Filmen enthaltenen Sex- und Gewaltszenen verwehrt und sie

sind nur als illegale Kopie auf DVD erhältlich.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/betano-casino-auszahlung-dein-umfassender-guide-fur-schnelle-gewinnauszahlungen/

December 21, 2025 @ 1:24 am

Dies bietet den Spielern die Gewissheit, dass sie in einer regulierten und geschützten Umgebung spielen. RocketPlay bietet eine große Auswahl an Glücksspielen aller gängigen Genres

und Formate. Das Casino bietet über 3.000 verschiedene Spiele sowie eine große

Auswahl an Spielautomaten, Kartenspielen, Roulette und mehr.

Das RocketPlay Casino mag viele Attraktionen haben, darunter eine Auswahl an Spielautomaten,

leistungsbasierte Dealer-Tische, Anmeldeboni und mehr.

Die Limits für Auszahlungen sind großzügig

gestaltet und bieten Flexibilität für unterschiedliche Spielertypen. Rocketplay Casino hat sich in kurzer Zeit als einer der führenden Anbieter im Online-Glücksspielmarkt für Deutschland und Österreich etabliert.

Das Support Team ist speziell geschult, um alle Aspekte unseres Casinos zu verstehen und schnelle, effektive

Lösungen zu bieten. Die PWA-Technologie eliminiert die Notwendigkeit, eine separate App herunterzuladen,

während sie eine App-ähnliche Erfahrung direkt über den Browser bietet.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/spinanga-casino-erfahrungen-ein-detaillierter-bericht/

December 26, 2025 @ 12:52 pm

Nowadays, it is not enough to just simply launch

your brand new online casino AU—it has

to be great from the get-go! The online casino

industry is getting more and more competitive each year.

We look at terms, max bonus, wagering, no deposit bonuses and many more

factors. In this list we have filtered out the absolute best Australian casino bonuses based on our

algorithm.

Now, if you don’t care much about themes and just want a solid casino that delivers good

and fair gameplay, King Billy checks all the boxes.

This Australian casino online does have table games,

but I had to use the search bar to find them. This

is amazing as it lets you see which games you are eligible to play with your bonus funds instead of reading the T&Cs, trying to find out.

There are over 20 bonuses for regular players, available daily and weekly,

on top of a loyalty program, a fortune wheel, and a 7% cashback bonus up

to $5,000. Good bonuses for both new and existing players?

Yes, all the casinos on my top list are legitimate, but Ricky

stands out because it has been around for a long time, pays players

consistently, and doesn’t delay withdrawals.

A classic card game, Blackjack challenges players to

beat the dealer with their strategy and luck.

These games offer life-changing winnings with jackpots that continue

to increase until they are won. Its strengths lie in the massive game library and crypto-friendliness, offering a modern gambling experience.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/luxor-las-vegas-in-depth-guide/

December 26, 2025 @ 3:24 pm

All in all, we ask you to give it a try, as the free bonus

may change your mind. On the other hand, the minimum deposit is

super low at €$5, which is a fantastic deal! It seems that not only live casino gamers are out of

luck today. It seems that there is no way that you can deposit your

funds using cryptocurrency. It seems that Gonzo Casino does not have a

very large bonus collection.

Korean Sex Watch online free Cowgirl orgasms and big cum in pussy by best

friend’s cock – Xreindeers Korean girl seduced in bed Pick up a sexy big tits lonely wife

on the street and have a passionate sex-cut

Erotic movie scenes collection korean asian 5.FLV Horny naughty asian girlfriend Here you can expect a

variety of fun and exciting offers, including Welcome Bonuses for new players, No Deposit Bonuses, and Cashback Bonuses.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/king-billy-casino-review/

December 26, 2025 @ 3:57 pm

The procedure ensures that only the legitimate account holder receives the winnings.

By requiring identity verification before the first withdrawal, we effectively prevent credit card fraud, identity theft, and money

laundering. Maximum weekly withdrawal limits reach $2,000 with higher amounts distributed across extended periods for exceptional wins, ensuring everyone receives their deserved winnings through structured payout schedules.

Get special bonuses when new games are released as well as additional bonus points when you deposit using the appropriate methods.It all starts

with a sign-up bonus and a four-part welcome package!

Ripper Casino offers a wide range of deposit

and withdrawal options to suit every player – but one of our specialities is catering to

all you crypto keen beans. Minimum cryptocurrency deposits are as small as $10 – and as little as $20 gets you a 150% bonus.

With generous welcome bonuses up to AU$7,500

and a mobile-optimized platform, you’ll never run out of exciting options.

Our curated selection of games, crafted by renowned developers, offers an unparalleled gaming experience that rivals the

finest establishments worldwide. These systems ensure that every spin,

roll, or card draw is completely random and unbiased, providing an honest gaming experience for all players.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/sign-in-your-gateway-to-online-casino-action/

December 27, 2025 @ 12:18 am

⟨a⟩ is the third-most-commonly used letter in English after ⟨e⟩ and ⟨t⟩, as well as in French; it is

the second most common in Spanish, and the most common in Portuguese.

However, ⟨a⟩ occurs in many common digraphs,

all with their own sound or sounds, particularly ⟨ai⟩, ⟨au⟩, ⟨aw⟩,

⟨ay⟩, ⟨ea⟩ and ⟨oa⟩. There are some other cases aside from italic type where script a ⟨ɑ⟩, also called Latin alpha, is used in contrast with

Latin ⟨a⟩, such as in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

The Roman form ⟨a⟩ is found in most printed material, and consists of a small loop with an arc over it.

In the hands of medieval Irish and English writers, this form

gradually developed from a 5th-century form resembling the Greek letter tau ⟨τ⟩.

Graphic designers refer to the Italic and Roman forms as single-decker a

and double decker a respectively. In some of these, the

serif that began the right leg stroke developed into an arc, resulting in the printed form, while in others it

was dropped, resulting in the modern handwritten form.

In Greek handwriting, it was common to join the left

leg and horizontal stroke into a single loop, as demonstrated by the uncial version shown. These variants,

the Italic and Roman forms, were derived from the Caroline Script version.

The names of the vowel letter u and the semivowel letters

w and y are pronounced with a beginning consonant

sound. The names of the consonant letters f, h, l, m, n, r, s, and x are pronounced

with a beginning vowel sound. Problems arise occasionally when the

following word begins with a vowel letter but actually starts

with a consonant sound, or vice versa. In algebra, the letter

“A” along with other letters at the beginning of the alphabet is used to represent known quantities.

In most languages that use the Latin alphabet, ⟨a⟩ denotes an open unrounded vowel, such as /a/, /ä/, or /ɑ/.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/new-online-casinos-australia-2025-guide/

December 28, 2025 @ 10:29 pm

online casinos that accept paypal

References:

https://cchkuwait.com

December 28, 2025 @ 11:10 pm

paypal online casino

References:

https://adm.astonishkorea.com

December 29, 2025 @ 6:54 am

paypal casino

References:

https://jobs.maanas.in/institution/paypal-payment-casinos-2025-canada-choose-your-paypal-casino/

December 29, 2025 @ 7:14 am

online pokies australia paypal

References:

https://jobsathealthcare.com/employer/best-us-online-casinos-that-accept-paypal-in-2024/

December 30, 2025 @ 12:38 am

australian online casinos that accept paypal

References:

https://www.inzicontrols.net/battery/bbs/board.php?bo_table=qa&wr_id=554970

December 30, 2025 @ 12:53 am

paypal casino sites

References:

https://jobteck.com.sg/companies/payid-casinos-australia-2025-find-best-payid-casinos/

January 20, 2026 @ 6:30 am

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.com/es/register?ref=RQUR4BEO

January 27, 2026 @ 11:43 pm

Материалы для взрослых доступны на различных сайтах для взрослых в развлекательных целях.

Всегда выбирайте надежные сайты для взрослых для защищенного опыта.

Feel free to surf to my web-site – ebony porn

January 28, 2026 @ 3:04 am

Порно доступны на различных сайтах для взрослых в развлекательных

целях. Всегда выбирайте безопапорно с черныминые платформы для защищенного опыта.

February 2, 2026 @ 2:47 pm

Reliable content, Thanks!