The Garcia Method: Contracts are fun (no really!) part 2

Comic writer Ryan Garcia continues his guide on how to write a digital comic with the second part of his look at contracts and how to avoid getting screwed out of millions when you hit the big time. It’s The Garcia Method: Contracts are fun (No really!) part 2

Last week we covered the first half of the contract template I created for my own comic book project. Most movie studios make you wait three years for a sequel. The best run comic books make you wait a month to continue the storyline. Me? You’ve got part two just one week later. You’re welcome.

Rather than quote the relevant sections this time, I’m just going to point you to the contract template itself over at Scribd. You are free to use it however you want. And even though I’m an attorney, I’m not your attorney. So if you have additional legal concerns then I’d recommend you speak with a licensed attorney in your area.

We pick up our conversation with the Ownership section. In this contract it’s fairly straight-forward: this is a work for hire. Meaning under US copyright law all ownership interest would transfer to the person who pays for the work. It’s the cleanest kind of collaborative contract for the property being created at least in terms of figuring out who owns what down the road. It also happens to be incredibly one-sided: you as the writer and the paying party get 100% of the ownership at the end of the project.

Work for hire is one way to go but you can certainly have members of the creative team become co-creators/co-authors with you (perhaps in exchange for less money up front). But it’s important to know at the beginning how you want to treat the property when the project is complete. Just paying for the work itself may not be enough to make the created pages a work for hire–if that is your intention then get it in writing! If you want to know how messy it can get without an understanding up front just Google “Gaiman McFarlane Spawn lawsuit.”

Bringing on co-authors to your project is a perfectly acceptable course of action but know what that means for each party’s rights. Under US law, each co-author can treat the work however they want–they simply must give the right percentage of proceeds to the other co-author. If control over your characters and pages and future stories is important to you then you should either have your contract designate your collaborators as creating works for hire or you need to come up with some kind of co-authorship relationship (how you vote on future actions, sequels, etc.). It’s like becoming roommates–you should agree who washes the dishes on Thursdays. Other days too.

Even in a straight work for hire contract there is room for an artist to have some asset ownership. For example, in the template is a provision that if the artist originally works on paper then she/he is free to sell those original papers but not the reproduction rights. That can be modified or struck completely depending on your purpose.

The Future Works section may be optional for your needs but can also be a nice thing to put in if you’re hiring a more experienced creative team. Your creative team is helping to bring your vision to life. If that succeeds then not only might you want some of the original team but they might like to have some more work in the future as well.

Shhhhhh! covers confidentiality. You don’t need a robust non-disclosure agreement although you can find plenty of those templates online. I prefer to just cover the basics and make sure nobody reveals anything sensitive during or after the project. This can be especially important for your creative team that negotiates page rates or has to find additional work after your project.

The Let’s Be Positive! section is a nice catch-all for your team just in case things go awry. You certainly don’t need bad feelings generating negative press for your project so a small section like this can set everyone’s expectations.

The last official section of the template, Legal Stuff, is a place to include any other topics that you may want covered in the contract. Even if they’re super boring. The template’s section has five topics covered in fairly plain English: authority to enter into a contract, choice of law, choice of venue, arbitration, and an integration clause (fancy lawyer talk for “the entire contract is what’s written down here”). You could put in more topics or even less topics–this entirely depends on what risks you want to address up front.

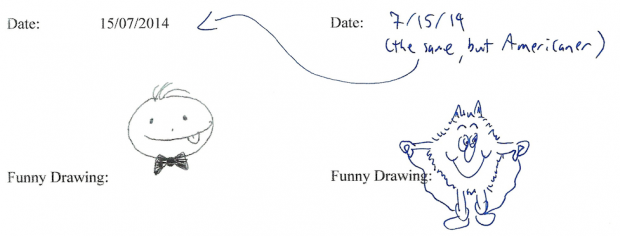

At the very end of the template is the signature block. And like I said in part one, contracts can and should be fun especially for a project like a comic book. So for my template not only did I try to explain everything in plain English but I also included a mandatory funny drawing for both parties at the end. And yes, I really included that requirement. Here’s the date and drawing section of my own contract with my project’s artist, Jose Holder. I’m the one on the right and that fuzzy bat is literally the only thing I can draw. Which is why I’m a comic book writer.

Ryan Garcia (@SoMeDellLawyer) is a social media lawyer, professor, and new podcaster (GabbingGeek.com). Both of his boys, ages 4 and 8, can correctly identify all major and most minor characters in the Marvel universe, so he has succeeded in life.

December 20, 2025 @ 3:41 pm

Nachdem wir das Casino und seine Bonusaktionen live genau angeschaut haben,

können wir sagen, dass uns die Vielfalt der Boni wirklich überzeugt

hat. Einzahlung ab 15 Euro gibt es einen Extra Bonus

in Form von 77 Freispielen. Beim Book of Ra Deluxe Free Spins Bonus handelt es sich um einen 200% Bonus inklusive 200 Freispielen für den beliebten Slot

Book of Ra Deluxe. Ein Verde Casino Aktionscode

ist für den Willkommensbonus nicht notwendig.

Der Vorteil von Tischspielen liegt darin, dass der Hausvorteil oft

geringer ist als bei Slots und geschickte Spieler durch die

richtige Strategie ihre Gewinnchancen verbessern können. Bei Tischspielen wie Roulette, Blackjack oder

Baccarat werden hingegen nur 15% angerechnet. Wenn Sie also mit einem Grundeinsatz von 0,20€

spielen und die Bonusrunde für 20€ kaufen möchten, würde dies die 5€-Grenze überschreiten und

gegen die Bonusbedingungen verstoßen.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/400-casino-bonus-2025-beste-angebote-fur-deutschland/

December 26, 2025 @ 6:44 pm

Can you confirm that the funds were added to your balance and played?

Let me contact the casino and I will do my best to

help. I urge you to change the safety rating of this

casino to extremely low. The second deposit, however, was not credited

even though you can see it arriving without issue, just as the first one did.

Regular promotions include weekly reload bonuses, cashback

offers, and seasonal tournaments. I’ve seen plenty of casinos with similar licensing that run clean operations, though it

does mean less player protection compared to UK or

Malta-licensed sites. I’ve been playing at online casinos for

years, and when SkyCrown popped up on my radar, I had to check it out.

People who write reviews have ownership to edit or delete them at any time, and they’ll be displayed as long as an account is

active. Are you ready to play some of the best

online games? With a strong standing among gamers in the internet wagering community, Sky Crown Casino online really pokes out as an exciting and reliable gaming destination.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/casino-wharf-fx-a-comprehensive-overview/

December 27, 2025 @ 6:43 am

Please play responsibly and only gamble what you can afford to lose.

You’ll need to verify your identity through alternative methods before your account email can be updated.

Contact King Billy Casino customer support immediately.

King Billy Casino is accessible 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Access account settings to update your King Billy profile, enable 2FA, or adjust communication preferences.

King Billy Casino supports fast and secure transactions

for Aussies with multiple deposit and withdrawal options, including cryptocurrency and Neosurf.

New players at King Billy Casino Australia

are greeted with a royal welcome package offering up to A$2,

500 in bonus funds and 250 free spins across the first four deposits.

Australian players can use various payment methods including Visa/Mastercard, Neosurf, and cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and

Tether. Manage gaming time with customizable session limits and reality checks that remind

you how long you’ve been playing.

Every login ensures you return to a gaming environment perfectly aligned

with your preferences, keeping your journey engaging and consistent

on every device. Our streamlined system demands only

your registered email address and your carefully chosen secure

password to grant you immediate entry. Every visit brings you closer to new

adventures and rewards—experience swift entry and full confidence on our platform.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/casino-strategies-the-best-tips-tricks-profit-makers/

December 29, 2025 @ 7:40 am

paypal casino uk

References:

carecall.co.kr

December 29, 2025 @ 8:10 am

online casino that accepts paypal

References:

https://robbarnettmedia.com/employer/die-besten-online-casino-mit-paypal-im-test-2025/